- Home

- Michael Wood

A South Indian Journey

A South Indian Journey Read online

PENGUIN BOOKS

A SOUTH INDIAN JOURNEY

Michael Wood, journalist, broadcaster and film-maker, has been acclaimed for his hugely popular BBC television series and the accompanying books In the Footsteps of Alexander the Great, and Conquistadors; the latest is India: a Journey in History.

Michael Wood

A SOUTH INDIAN JOURNEY

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, So Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England.

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell,

Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.co.uk

First published by Viking 1995

First published in Penguin Books 1996

This edition published in Penguin Books 2007

I

Copyright © Michael Wood, 1995, 2007

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-193527-0

To Rebecca

Contents

Map of Tamil Nadu

Introduction

Prologue

Part One: THE COOL SEASON

1

Mala

2

The Astrologer

Part Two: THE SEASON OF RAINS

3

Madras

4

To the South

The City of the Cosmic Dance

The Lord of Healing

The Family House

5

The Video Bus

Rameshwaram

Tiruchendur

Cape Comorin

Suchindram

Courtallam

Srivilliputtur

The Rock of Sikander

The Great Goddess of Madurai

The Hill of Palani

6

Journey into the Delta

The Cyclone

Kumbakonam

Tanjore

The Bronze Caster

Suryanarcoil

The Dance

Saturn

To the Sea

Part Three: THE TIME OF RIPE HEAT

7

Chidambaram

8

Madras

9

Taramani Sunday

Epilogue

Indian Gods and Goddesses

Glossary

Introduction

This book tells the story of a series of journeys in Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state in India, which stretches down to the tip of the subcontinent, opposite Sri Lanka. This is a land which many visitors since Marco Polo’s day have thought one of the most splendid and fascinating on earth, and my simple aim in writing was to give the general reader, and the traveller, a flavour of the beauties of Tamil culture, and of the southern landscape. I have called Tamil Nadu the last classical civilization, by which I mean a civilization in which a substantial element of the traditional ways of thinking – in belief, culture, music, and literature, for example – is still alive in the mainstream, however pervasive the impact of modernity and global culture may be in India today.

The book is also about a friendship between my family and an Indian family in a small town in India’s deep south. This friendship came about as a result of a chance meeting with Mala and her family when my wife and I arrived in the ancient town of Chidambaram as travellers one Diwali twenty years ago. Hers is a traditional Saivite family belonging to the agricultural caste which supported the Cholan kings in the great age of Tamil culture in the ninth and tenth centuries, and who have devotedly carried down the beliefs and aspirations of their caste till today; people who are playing their part in the dynamic world of modern India, but who also still live in sacred time. In the epilogue this new edition brings the story of Mala and her family into the twenty-first century.

I would like to thank the many friends in Tamil Nadu who helped me write this book and who, more importantly, gave me their friendship over a dozen visits to their country: chiefly M. Nagaratinam and family; R. Sushila and family, Lakshmi Vishwanathan; Dr R. Nagaswamy; the priests of the Nataraja temple, in particular R. N. Dikshithar and Rajdurai Dikshithar; the staff of Hotel Tamil Nadu, Chidambaram; Dr R. Baskaran and family, and all those who travelled on the 1992 pilgrimage to Tiruchendur and in 1994 to Palani. Lastly I would like to thank the staffs of the various temples in this story who kindly allowed a non-Hindu access to their shrines. To all my grateful thanks. I hope they will understand and forgive such liberties as I have taken in the story with time and place. In England I would like to thank Pru Cave, John Collee and Stuart Blackburn for their helpful comments and criticisms. I would also like to thank two scholars whose work has inspired all who love Tamil culture: Kamil Zvelebil for a title, and David Shulman, for a beginning; also Gabriella Eichinger Ferro-Luzzi for help with Mr Ramasamy’s jokes: I hope all three will look kindly on my magpie borrowings. Last of all my greatest debt is to Rebecca Dobbs for her love, encouragement and understanding, and to our daughters Jyoti and Mina, without whom this journey would never have happened.

Prologue

For a long time when we came to Madras we used to stay in a room in a tower block, J.P. Tower, down Nungambakkam High Road. A ten-storey warren of flats and small businesses, it was only built in the late seventies, but already its yellow walls were stained black by the relentless heat and the monsoon rains. The auto-rickshaw would stop on the corner of a narrow dirt lane which led to the entrance to the building. You climbed out by a heap of rotting vegetation and soggy cardboard chewed over by a thin white cow which, like the rubbish, never seemed to move from this spot. Over the lane a new hotel was built in the mideighties with a liquor permit room at the back – Tamil Nadu was still a dry state in those days – and along with the cow, there would always be a doorkeeper in khaki fatigues and military beret on duty by the gate. Inside, when the clinging heat of the Madras night put its hand on your shoulder, there was chilly air-conditioning, and beer so cold it took your breath away.

Inside the tower block the foyer had a lingering aroma of DDT and incense. One lift was always out of action but, miraculously, one always worked. It was operated by a barefoot lift boy with a sweet smile, who never lined the lift up with the floor, so that you usually had to crouch to get out. (I never understood why; I had a crazy notion this was some kind of tactic because of the power cuts.) We used to stay on the fifth or sixth floor, I can’t remember now: a cluster of rooms for travelling salesmen which was dignified by the name of the Krishna Executive Lodge. It had be

en booked for us by a Tamil friend who worked in an office on the floor below. The rooms were very clean, if mosquito ridden; the lady at the desk was very quiet and patient, always game to spend half an hour trying to get a trunk call for you, before disappearing to another floor to do the mysterious other job which occupied most of her day. The boys, on the other hand, were quite unsuited to running such an establishment; they were ever helpful and always smiling, but insisted on turning on the TV at full volume at the crack of dawn while they prepared cardboard toast and muddy coffee.

The place was handy for midtown: in ten minutes you could walk to the restaurants and bookshops down Dr Radakrishnan road, under the flyover, where the sleepers on the street live on concrete ledges inches away from the traffic, cooking their evening meals on wood fires at the feet of the huge, hand-painted movie hoardings which line the road. Near by was Mr Balasubrahmanian’s Carnatic Music Bookshop, a treasure house of traditional Tamil culture, its shelves sagging under texts of Thyagaraja and the other ‘modern’ greats of southern music. Here too were books on the classical dance and, in the back, stacks of literary, philosophical and religious classics: grammars, glossaries, epics, poems on love and war, medieval treatises on literary theory, the songs of the saints (which are still memorized in traditional families). These are all part of a continuous two-thousand-year-old tradition which is virtually unknown in the West, one of the world’s last surviving classical cultures. And as if to to remind you of its wellspring, in the front room of the shop was a a little shrine with puja lamp, bowls of camphor and incense, and a picture rail lined with old gilt-framed pictures of the gods. Here Mr Balasubramanian did his prayers every morning before opening.

Close by was the Music Academy, where you could go to concerts of classical dance, Bharata Natyam – an art form now enjoying a renaissance after its suppression in the temples by the British in the early years of the century. And round the corner there was Woodlands Restaurant, where the vegetarian tradition of the south could be sampled, eaten with the hand from plates of fresh plantain leaf. The enduring connections with the British period may give India a strange familiarity to the visitor from these islands, even in the most unlikely places, but the newcomer to the Tamil south does not have to venture very far from his or her hotel to see that this is a wholly different civilization, which has survived to take modernity on something like its own terms.

The best thing about J.P. Tower was the view. To see it you had to climb up the stairwell, glimpsing through open doors some of the strange clientele of the upper floors: one-room import–export offices, astrologers, shipping agents and a specialist in sexual problems (‘MD, Mysore’). Past the room for the lift machinery there was an inspection door on to the roof. Outside you had to scramble over a jumble of air-conditioning pipes, building debris and pools of dried concrete, and then duck under washing lines snapping in the breeze which comes up from the sea in the late afternoon. At the railing you found yourself looking southwards over the wonderful urban landscape of south Madras: growth and decay intermingled, growing out of each other. Near by another tower block was going up: this was the beginning of the new boom years for the city. Labourers clambered barefoot over a forest of wood and bamboo scaffolding, baskets of bricks on their heads. Tiny white loincloths, red headbands, sweat glistening on ebony backs. The construction method can hardly have changed for a thousand years; temple towers and skyscrapers alike are thrown up with crazy webs of timber and bamboo poles lashed with coir rope, which look as if the slightest puff of breeze would blow them down.

Further out you could see a city of gardens, a green sea of palms dotted by the spires, domes and pavilions of the old British suburbs around Adyar Park, the Madras Club and the river. Looking southwards the first time, I found this view simply heart-stopping. And ever since then it has seemed to me like the threshold of a magical land. The sun sinks to the horizon, an orange ball, and the sky turns soft peach to the south-west, shading to a ripple of gold with translucent ultramarine above. Thirty or forty miles away on the horizon you clearly make out the red hills of Tirukalikundran, tipped by the spire of its ancient temple. There, every day towards twelve, two eagles come to be fed from bronze bowls by Brahmin priests in a mysterious ritual which was reported nearly four hundred years ago by European visitors. Always around midday; always two eagles – never one or three. It is one of those strange Indian fairy tales (like rope tricks, snake charmers and self-mortifying fakirs) about which we read in our childhood books – and which turn out to be ‘true’. A foretaste of the wonders and illusions which lie beyond.

Those distant hills mark the gateway to the south. From Madras it is five hundred miles down to the tip of India at Cape Comorin, where the Arabian Sea meets the Bay of Bengal. To the west and north-west, the Tamil country rises to high wooded mountains, the Western Ghats and the Cardamom Hills, which still abound in wild beasts. There the British built their hill stations, like Kody and Ooty, to escape the ferocious heat of the plains. But the heartland of the south is the flat country of the Coromandel coast, cut by the rivers Pennar, Vellar, Cavery and Vaigai. This is where Tamil civilization grew and flowered – ‘the most splendid province in the world’, Marco Polo called it. It is a land of dazzling emerald-green rice fields and immense palm forests, where at almost every railway halt the temple gateways tower above the trees like petrified vegetation, ancient centres of myth and religion which are still part of a living sacred landscape, ‘India’s Holy Land’. It is still, for those susceptible to enchantment, an enchanted country: a ‘land where it all comes back’, as an old India hand once said to me, ‘the stuff of your karmic dreams’. This is the story of a journey through that land, down to the southern tip of the subcontinent, through the landscape – physical, mental, imaginal – of the Tamil universe; one of the last – perhaps the last – of the classical civilizations to survive to the end of the twentieth century. The journey started long ago, one Christmas. And it started with a prediction.

Part One

THE COOL SEASON

Mala’s house lay in a dusty street of beaten earth, hard beneath the feet, heavy with sun. Chidambaram is really just a big village clustered round the temple; and hers is a village street lined with ancient wooden houses with thatched roofs, little latticed verandas and pillared porches. At the threshold of the house every morning she laid out a kolam, a pattern in rice flour on the swept floor: intertwined geometric shapes, a flower, a peacock, a maze, auspicious signs to protect the home. Here in the south, the unseen is always palpable, and is always threatening to break in upon the present; it can never be ignored.

It was Mala’s choice to live here, so as to be close to the great temple of Nataraja. For south India’s Saivites, devotees of the Great God Siva, this is the holiest of all shrines, where the god is enthroned as Lord of the Dance in the golden-roofed sanctum whose origins, it is said, lie back in the remotest antiquity. The immense rectangle of the temple dominates the town, and its towers can be seen for miles across the flat landscape of the coastal plain; at night, when their lamps are lit, they are landmarks to sailors out at sea. After her husband lost his sight, Mala returned here, to the place where she was born, to bring up her children, and to be near Nataraja. Sometimes her devotion drove the girls to distraction. There was nothing much for them in Chidambaram. Life would be better in Madras or Pondi. But as Bharati always said, ‘Mother would never leave Nataraja’.

Every day without fail Mala would go into the temple at six in the morning when the air is still cool, walking barefoot through the spacious courtyards to hear the music and see the flame lifted to Siva’s eyes. And again at ten, for the offerings of honey, milk and coconut, and then in the evening when the age-old Tamil hymns are sung by the oduvars, hereditary singers from the middling castes like her own, who must stand outside the sanctum, for this is the preserve of the Brahmins with their Sanskrit rituals. Even when she was away, Mala could tell you to the minute which of the events of the temple’s ritual d

ay was under way. It was a rhythm as ingrained in her daily life as waking, eating and sleeping, and I suspect it gave her as much sustenance.

Mala’s house was a few minutes’ walk from the East Gate of the temple. She had a single room with a lean-to tiled roof around which lizards and rats scampered; a row of triangular air vents in the bricks allowed a little breeze in the hot weather. Inside there was enough space for a wooden bed, a folding camp bed, a metal chest for the family treasures, a treadle sewing-machine and a small table. When everyone was at home the children slept on the floor. On the walls she hung brightly coloured religious posters depicting her favourite gods and goddesses: many-armed creatures with kohl-dark eyes and dreamy smiles, garlanded with flowers, their saris seamed with gold. Above the bed was an out-of-date calendar from a sparking plug firm in Madras, with a picture of the god who is beloved of all Tamils, Siva’s son, the divine boy-child, Murugan: a beaming cherub with a plume of peacock feathers. At the other end of the room there was a narrow kitchen space behind a five-foot-high brick partition; here she had a Calor gas burner, stone shelves for pots and pans, a vegetable basket, a grinding stone and pestle. Outside her door a communal passageway led to a latrine, a well and a small tank for rainwater. In this confined space, the surrounding streets and shops, and the temple itself, most of her daily routine passed.

The Story of India

The Story of India Stolen Children

Stolen Children In Search of the First Civilizations

In Search of the First Civilizations The Murder House

The Murder House A Room Full of Killers

A Room Full of Killers In Search of the Dark Ages

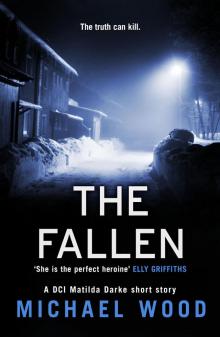

In Search of the Dark Ages The Fallen

The Fallen Time Is Running Out

Time Is Running Out A South Indian Journey

A South Indian Journey In Search of Shakespeare

In Search of Shakespeare The Hangman's Hold

The Hangman's Hold For Reasons Unknown

For Reasons Unknown Outside Looking In

Outside Looking In