- Home

- Michael Wood

In Search of Shakespeare

In Search of Shakespeare Read online

Contents

Cover

About the Book

About the Author

Praise

Title Page

Prologue

ONE

ROOTS

TWO

A CHILD OF STATE

THREE

EDUCATION: SCHOOL AND BEYOND

FOUR

JOHN SHAKESPEARE’S SECRET

FIVE

MARRIAGE AND CHILDREN

SIX

THE LOST YEARS

SEVEN

LONDON: FAME

EIGHT

THE DUTY OF POETS

NINE

‘A HELL OF TIME’

TEN

SHAKESPEARE IN LOVE?

ELEVEN

SHAKESPEARE’S DREAM OF ENGLAND

TWELVE

AMBITION: THE GLOBE

THIRTEEN

THE THEATRE OF THE WORLD

FOURTEEN

GUNPOWDER, TREASON AND PLOT

FIFTEEN

LOST WORLDS, NEW WORLDS

SIXTEEN

TEMPESTS ARE KIND

Epilogue

Picture Section

Further Reading

Index

Acknowledgements

Picture Credits

Copyright

About the Book

The greatest writer of the English language as he lived and breathed – a spellbindingly immediate portrait of William Shakespeare and his world.

Almost four hundred years after his death, Shakespeare is still acclaimed as the world’s greatest dramatist, yet the man himself remains shrouded in mystery. In this newly updated edition of his acclaimed biography, broadcaster and historian Michael Wood looks afresh at Shakespeare’s life, brilliantly recreating the turbulent times through which the poet lived. Marked by murderous plots and state terror, religious divisions and rebellious movements, Shakespeare’s world is conjured up here like never before.

About the Author

Michael Wood was born in Manchester and educated at Manchester Grammar School and Oriel College, Oxford, where he did postgraduate research in Anglo-Saxon history. A broadcaster and filmmaker, he is the author of several highly praised books on English history, including In Search of the Dark Ages, The Domesday Quest and In Search of England. He has over eighty documentary films to his name, including Art of the Western World, Legacy, In the Footsteps of Alexander the Great, Conquistadors, In Search of Shakespeare and In Search of Myths and Heroes. The writer behind three BBC films about Shakespeare’s early history plays, he was a contributor to Shakespearean Perspective (1985). Michael Wood is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society.

‘In this enthralling book, Michael Wood evokes the physical and intellectual environment in which Shakespeare lived and worked with vivid and original immediacy.’

PROFESSOR STANLEY WELLS, Editor of The Oxford Shakespeare

‘There are many books on Shakespeare by professional academics that are full of bright ideas and interesting information, but which lack the arts of the man himself: bringing characters and places to life, grabbing the audience through story-telling, transforming complex intellectual debates into the immediacy of drama ... Thanks to Michael Wood’s gifts as a story-teller, populariser and interpreter of the past, Shakespeare’s world is brought alive more vividly than in any other biography of him that I have read.’

JONATHAN BATE, Sunday Telegraph

‘An evocative and occasionally enchanting retelling of the known facts, which are, in reality, numerous. On the question of whether Shakespeare was a secret Catholic like his father – now, much discussed, especially among Catholics – Wood is at his eloquent best. He describes vividly the insecurity of the changing times ... A perceptive, entertaining companion, his account of the late plays conjures a poignant farewell to a playwright we would love to have known.’

FERDINAND MOUNT, Sunday Times

‘Wood has now brought his unusual talents for research and exposition to the subject of Shakespeare and his times. The results are ... exciting [and] tendentious ... His account of the London of Shakespeare’s day is excellently done, and interestingly illustrated, sometimes with 19th-century photographs of Jacobean streets and buildings long since destroyed.’

SIR FRANK KERMODE, The New York Times

‘Michael Wood has distilled the dangerous mix of scholarship and controversy to conjure up a Shakespeare who is inspired and practical, engaging and mysterious. Wood’s Shakespeare is above all believable and will create the popular image of the Elizabethan past for the next generation.’

PROFESSOR KATE McLUSKIE, Director of the University of Birmingham’s Shakespeare Institute in Stratford-upon-Avon

’Wood succeeds in putting together a complete account of the greatest poet and dramatist in history, one that is both convincing in its narrative and compelling in its detail.’

BBC History Magazine

‘Michael Wood is such an accomplished popular historian that he could write about anything and readers would pay for the finished product. Wood shows that though there isn’t a huge amount of documentary evidence about Shakespeare’s life, there is enough to place his extraordinary talent in its proper historical context. A lucid, extended footnote to the complete works of the world’s greatest writer.’

BARRY FORSHAW, Publishing News

‘This wonderful book transports us back to the world in which Shakespeare lived and worked. Wood uses previously unexplored archive evidence to shed new light on the bard’s life, which remains shrouded in mystery, and in so doing brilliantly recreates the sights and sounds of 16th-century London. This vivid text, with stunning breadth of research and information, is both intellectual and entertaining ...’

Good Book Guide

‘Wood has crafted a book of substance and originality. Combing a wealth of scholarship and a bit of his own sleuthing, Wood presents a portrait of Shakespeare as very much a child of Stratford, a poet from whom the people and countryside of his youth were always a part of his conscious, creative life. We are also given a convincing portrait of the artist’s struggles in the unpredictable world of the Elizabethan theatre ... A highly readable, informative, and artfully illustrated volume for bardolaters and common readers alike.’

Booklist

‘This life of Shakespeare has all the vividness of a good television profile, backed up with a keen and contentious historical perspective on his turbulent era ... As an old medieval hand Wood positions Shakespeare on the cusp of the modern age, but with a firm background in the old traditions. He’s also superb at bringing together the Warwickshire idiom and rural nomenclature that runs through the plays. Wood brings 16th-century London to raucous life [and] throughout Shakespeare is treated as a living person inhabiting his time.’

US Publishers Weekly

PROLOGUE:

‘THE REVOLUTION OF THE TIMES’

IN THE WINTER of 1563, four or five months before William Shakespeare was born, his father was called upon by the corporation of his home town to oversee a troubling task. John Shakespeare had served Stratford diligently as constable and ale-taster, and was now the chamberlain or treasurer, responsible for the town accounts. And on a cold day in the darkest time of the year it was his job to hire workmen, with ladders, scaffolding poles and pots of limewash, to desecrate the town’s religious images: to destroy the medieval paintings that covered the walls of the guild chapel, next door to the guildhall and the school.

In the old days, before King Henry’s time, the chapel of the Guild of the Holy Cross had been the centre of Stratford’s civic life and ceremonies. The guild had endowed and run the grammar school, held feasts, disbursed charities and run the town’s almsh

ouses. Inside the chapel, every inch of wall was covered with splendidly gaudy paintings depicting tales loved by all English people, stories rooted in the fabric of the nation’s culture for nearly 1000 years. There was St George and the Dragon, the Vision of the Emperor Constantine, and St Helena and the Finding of the True Cross, the subject of Old English poetry 700 years earlier and more recently retold in Caxton’s Golden Legend, one of the first books to be printed in English. Near the door were images of local female saints, familiar friendly intercessors, such as Modwenna, whose sacred well at Burton-on-Trent was still much visited by traditional folk in Warwickshire. There was a depiction of the murder of Thomas Becket, whose great pilgrimage had been immortalized by Chaucer. Over the nave arch was a painted wooden crucifix, the Holy Rood, and behind it a great mural of the Last Judgement: Christ seated on a rainbow, the world as his footstool, with souls on their way to heaven, hell or purgatory, red-hot chains encircling the damned, alongside the seven deadly sins and devils blowing horns and wielding clubs: images of warning and consolation, of fear and bliss.

These were the stories of John Shakespeare’s childhood and youth in the first half of the sixteenth century. Like most countrymen of his age, his mental world had been shaped by the traditional Christian society of England: the old rhythms of the farming seasons and the religious calendar, and the feasts and holy days that accompanied them. But such things were now officially condemned as childish superstition. At the start of Elizabeth’s reign a royal injunction had instructed town councils to enforce ‘the removal of all signs of idolatry and superstition, from places of worship, so that there remain no memory of the same in walls, glasses, windows, or elsewhere within their churches and houses’. The aldermen of Stratford had put it off for five years, but now the time had come. Whatever his private feelings, it was John’s duty to vandalize images that represented a world of encoded memories built up over the centuries. These were the familiar and beloved observances of his parents and grandparents, a vast and resonant world of symbols that linked him to the ancestors and to the old idea of the community of England.

How had it come to this? It’s the kind of thing we associate with the religious conflicts that mar our modern world, the rage of iconoclasts – but this was in England. It had been Elizabeth’s father Henry VIII, back in the 1520s and 1530s, who had begun the revolution that would turn England from a medieval Catholic society into a modern Protestant state. Henry’s Reformation had begun with his love for Anne Boleyn and his desire for a divorce from his first wife, Katherine of Aragon. A battle for supremacy resulted: who was the ultimate authority in his kingdom, the king or the pope in Rome? Eventually this led to the breaking of the link with Rome, which had been maintained steadfastly by the English since the mission of St Augustine in 597 to convert them to Christianity. In pursuit of his divorce, the king made himself supreme head of the Church of England, in place of the pope. Henry had intended change to stop there; and so it might have done, but for two things. First, in 1536 Henry’s money troubles led to his seizing the lands, buildings and treasures of the monasteries, many of which went back to the beginnings of English Christianity. The second major factor was the influx of new Protestant ideas from Germany, where Martin Luther had defied pope and emperor and become a national hero. For Luther the way to God was a matter of individual conscience grounded in scripture, that did not need either the institution of the Catholic Church or its ‘superstitious’ doctrines, which he perceived as chains to bind the simple-minded. The dissolution of the monasteries and the Protestant Reformation that followed inaugurated a permanent shift of power in England, the creation of an absolutist state and a new landed class that would have a vested interest in supporting the new regime and its state religion. Out of these convulsions, involving religion, class conflict and civil war, modern secular Britain would emerge.

But at grass-roots level in towns such as Stratford, and in the countryside round about where John Shakespeare grew up, little had changed by the time of Henry’s death in 1547. In the years after the break with Rome a half-Protestant, half-Catholic Church with a Protestant prayerbook had been established. It was in the short reign of Edward VI, Henry’s son from his third marriage, to Jane Seymour, that the real revolution began. Edward was a pious, cold-hearted swot, who was surrounded by a tight-knit group of politically motivated men. Now the fury of destruction that had visited the monasteries fell on all churches, cathedrals and chapels, which he ordered to be stripped of their screens, statues and paintings. In many places, however, the pace of such change was slow, and when Edward died in 1553, still in his teens, his half-sister Mary, daughter of Katherine of Aragon and an ardent Catholic, became queen. Greeted with a burst of enthusiasm on her accession, Mary soon lost public goodwill because of her intolerance. She attempted to reverse Henry’s revolution, to turn the clock back, and in her brief time on the throne she earned the name Bloody Mary by burning Protestants up and down the land. In this story, terrible things were done in the name of God by England’s rulers on both sides of the religious divide.

So when Mary died and Elizabeth, daughter of Henry’s second wife, Anne Boleyn, came to the throne in 1558 the country was caught between old and new. Elizabeth was a convinced but not zealous Protestant. This brilliant, vulnerable and psychologically damaged monarch gambled that she would outlive the troubles she had inherited, and with her advisers set out to return the country to the path of her father’s and half-brother’s ‘reformation’ of religion.

Back in Stratford in that winter of 1563, then, they had gone through three changes of religion in less than twenty years when John’s workmen began to cover up the great cycle of medieval paintings. With that the story was supposed to be over: in Elizabethan terms it was the end of history, or of one version of history. Such at least was the government’s intention. The town was to lay its past aside, put its best foot forward and walk into a brave new Protestant future. Its children, the next generation such as John’s son William, were to be obedient citizens of Elizabeth’s reformed state.

But was that really how it was? It is generally believed that the defacing proves Stratford was by then a Protestant town, and John himself a conforming member of the Church of England – even a zealous one. But scrutiny of the town minutes reveals a rather different story. The corporation of Stratford and their treasurer in fact left all the stained glass in place and refused to sell off their finely embroidered vestments and cloths. They left wall paintings untouched where they thought they could get away with it, and even partitioned off the chancel so that none of the paintings there was destroyed – they were still visible on the eve of the Civil War in 1641. And as for those images defaced that day, they were so thinly covered over that they were still vivid and intact when discovered centuries later. So John had acted contrary to the 1559 injunctions, leaving images ‘slubbered over with whitewash that in an hour may be undone, standing like Diana’s shrine for a future hope and daily comfort of old and young papists.’ The work, then, was reversible, and surely deliberately so. After all, no one in Stratford at that moment knew which way history would go.

So here’s a parable at the start of our tale, but one full of ambiguity. What lies under the whitewash? What lies behind actions and words in an age when covering up, concealment and dissimulation became the order of the day? Such questions are as relevant to the life of the greatest poet of all time as they are to untangling the tale of his father and his neighbours in his home town.

This is the tale of one man’s life, lived through a time of revolution – a time when not only England, but the larger world beyond, would go through momentous changes. In one of her most famous painted portraits, Elizabeth stands on a map of little England with her foot on Ditchley in Oxfordshire – a huge figure on a small country. And when Shakespeare was born her England was a small place, nothing compared with the great contemporary powerhouses of civilization: Moghul India, Safavi Iran, Ottoman Turkey and Ming China. When the Persian Shah a

nd the Great Moghul stand on their map in another emblematic picture of the age, the world beneath their feet spreads from China to the Mediterranean, embracing the old heartlands of civilization. England, with a population of less than 3 million, was an old-fashioned, backward place out on the fringe of Europe. But as the centre of gravity of history began to shift, as the old civilizations of Asia were outflanked by the new maritime states of the Atlantic seaboard, England’s moment was about to arrive.

Shakespeare, then, was lucky to be born on the cusp of history. If he had been born in his parents’ generation, two or three decades earlier, his mind might not have been open to the challenges of the modern world; a few decades later and he would not have been in touch with the old world view, the imaginal universe of the medieval Christian civilization of England and Europe. Shakespeare may be, as has been claimed in our time, the first modern man, the creator of our modern idea of personality, the ‘inventor of the human’, but he was also the last great product of the Gothic Christian West. If great writers are made by their times, then to be born in 1564 was to be born in very interesting times indeed.

Such dramatic changes would provide the raw material for the artists, poets and thinkers of Shakespeare’s lifetime, a time that would lead to civil war and the execution of the king. And from the macrocosm to the microcosm, these ideas run through Shakespeare’s works. New worlds are discovered, old worlds are lost; the people rise up; kings are overthrown; women speak up for equality with men; black people find a voice in England. Ships sail across the world loaded with people, spices and ideas; potatoes rain out of the sky; tales are told of Lapland sorcerers, Persian emperors and embassies to the Pigmies. Off Sierra Leone, African dignitaries watch Hamlet on a British ship; the Native American princess Pocahontas attends a masque in London. Then as now, globalization means that ideas are globalized too.

The winter light is falling over Chapel Street as the last lime is sloshed over Christ’s rainbow throne and drips down the face of Jesus. The workmen untie the ropes on the scaffolding, looking forward to their wages and a jug of ale in Burbage’s tavern in Bridge Street. John Shakespeare stamps his feet to keep warm in the chilly chapel. The job is done, to be entered into his January account along with repairing the vicar’s chimney and mending the bell rope: ‘Item payd for defaysing ymages in the chappell iis’ (years later, uncannily, his poet son would write of ‘defacing the precious image of our dear Redeemer’). At this moment, in Stratford in the winter of 1563–4, John Shakespeare might not have been able to see it yet, but the world was poised between old and new, between no longer and not yet; or, as his son would put it, between ‘things dying and things newborn’.

The Story of India

The Story of India Stolen Children

Stolen Children In Search of the First Civilizations

In Search of the First Civilizations The Murder House

The Murder House A Room Full of Killers

A Room Full of Killers In Search of the Dark Ages

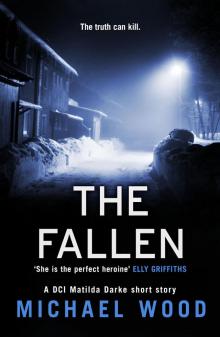

In Search of the Dark Ages The Fallen

The Fallen Time Is Running Out

Time Is Running Out A South Indian Journey

A South Indian Journey In Search of Shakespeare

In Search of Shakespeare The Hangman's Hold

The Hangman's Hold For Reasons Unknown

For Reasons Unknown Outside Looking In

Outside Looking In