- Home

- Michael Wood

In Search of Shakespeare Page 3

In Search of Shakespeare Read online

Page 3

Even luxury goods were to be found now. On their boards shopkeepers sold goods imported into London and carried here by the Greenaways’ pack trains: fruit and nuts from the Mediterranean and soon potatoes from Virginia. The growth of a new middle class encouraged specialized trades: people were beginning to covet smart clothes, for instance. The opportunities were here, not driving an eight-ox team up and down a piece of ploughland at Snitterfield. And it was here that John Shakespeare made his career as a glover.

The earliest record of John in Stratford is in a document of 1552, the first case in a long career of litigation that seems to have run in the Shakespeare family. He was fined for leaving a ‘dung heap’ – a rubbish tip – in Henley Street; perhaps a rotting heap of leather shavings and offcuts. Once he had done his apprenticeship, John became a bespoke glover who sold his work on a stall with the other glovers at Market Cross. He would have cut and worked the leather in his own home – quite a cottage industry, perhaps, with outworkers, and with women in his outhouse doing the sewing.

As late as 1561 he appeared in the Snitterfield post-mortem of his father as agricola, a farmer, but by then he had risen in social status in Stratford and become a town councillor, justice of the peace, constable and ale taster. By then, this ‘merry cheeked man who durst have cracked a jest at any time’ had become part of the town’s ruling elite and was clearly a popular and respected man of good judgement and capacity. So the Snitterfield farmer was now a member of Elizabeth’s new civic order, part of what they called the ‘commonwealth’ of England. It seems he never learned to write: he always signed with a mark depicting the glovers’ compasses or the ‘donkey’ on which leather was stretched. But he must have had basic reading skills simply to fulfil his civic role, let alone to keep his account books.

English local government was part of a very old tradition of consultation and representation; looking after what, even three centuries before, had been known to well-to-do peasants as ‘the welfare of the community of the realm’ – a national community personified by the monarch, who was the focus of their allegiance provided that he or she was sensitive to local feelings. John’s twenty-four fellow-councillors or aldermen were middle-class propertied sorts: glovers, hatters, haberdashers. Meetings were held behind closed doors in the guild rooms. The job of the council was to run the town: to supervise education and ensure cleanliness; to look after the poor, sick and unemployed; and to keep order and resolve conflicts. Its members were reimbursed for expenses, but not paid. They were not expected to refuse office, nor could any of them resign their appointment; it took a serious misdemeanour or a dramatic falling out to be struck off, as John would eventually be.

His role as town councillor is significant for his son’s story, for Shakespeare’s father and his colleagues were compelled to engage with national politics and history. As representatives of central government they had to control, to encourage conformity and to identify dissent. They were the people whose fate it was to negotiate change, to guide the town through the dangerous times of the Catholic Queen Mary and her Protestant successor Elizabeth; times in which England would be changed for ever.

THE ARDENS: SHAKESPEARE’S MOTHER’S FAMILY

In the late 1550s – at the end of Queen Mary’s reign – John was probably getting on for thirty. The average age for a man to marry in Tudor England was twenty-eight, and twenty-six for a woman. So off he went to seek a wife. She was the daughter of his father’s old Snitterfield landlord, a girl he might have known since childhood: Mary Arden.

Shakespeare’s mother adds another dimension to the poet’s biography, in terms of his cultural and social background. For Mary came from a family of real status in Warwickshire, with links to some of the powerful Catholic families in the shire. For a start – and how could this not have impressed itself upon a child? – they bore the ancient name of the forested region of Warwickshire north of Stratford. According to seventeenth-century local antiquarians, the Ardens traced their ancestry back to the Anglo-Saxon lord Thurkill of Arden (and, according to Domesday Book, their land at Curdworth was indeed held by Thurkill in 1066). But tradition took them back further still to legendary figures such as the hero Guy of Warwick, who figured in poems of the sixteenth century that William Shakespeare certainly knew. The Ardens’ ancestry reinforced the family’s sense of national history. Thomas Arden had fought for the Barons and Simon de Montfort in the civil war of the thirteenth century; Robert Arden, who had fought for the Yorkists in the Wars of the Roses, had been executed in 1452. More recently John Arden, Mary’s great-uncle, had been in service at the court of Henry VII as an Esquire of the Body. The family even had a room in Park Hall, their house at Curdworth 20 miles away, called the King’s Chamber – perhaps Henry had actually stayed there.

There is still some uncertainty over Mary Arden’s exact relation to the Park Hall Ardens, but the evidence suggests she was descended from Thomas Arden, one of several younger sons of Walter Arden of Park Hall, who recovered the family estates during the Wars of the Roses. Thomas had land in Warwickshire at Wilmcote and Snitterfield. His son Robert, who farmed in both places, was called a ‘gentleman of worship’ by Shakespeare in his submission to the Royal College of Arms in 1596. That was to rewrite history a little. In reality Robert was just a well-to-do local farmer who called himself a husbandman. But, however distantly, he came from an ancient family, and he was the father of Mary, the poet’s mother.

MARY ARDEN’S CHILDHOOD HOME: A PLACE OF SUBSTANCE

Thanks to a fascinating piece of archival detective work, the house in which Mary lived up to her marriage was identified in 2001 as Glebe House in Wilmcote, four miles north of Stratford. The house has a Victorian brick skin, but up on the second floor is Tudor lath and plaster, and beams whose tree rings reveal they were cut in 1514. It started life as a plain hall house 55 feet long with an open hall in the middle, and a chamber with a bedroom floor at one end and the kitchen at the other; outside was a workshop. In the yard stood cattle and hay barns, a stable, a well and a privy. Mary’s father had about 135 acres, with another holding of 30 acres called Asbies and further land at Snitterfield. It was a sizeable holding for a husbandman of the day.

So Mary, one of seven sisters, grew up as the daughter of a prosperous farmer and bearer of the oldest name in Warwickshire. By a great stroke of luck Robert Arden’s will, dated November 1556, survives in Worcester Record Office. Mary, then still unmarried, was the executrix: a clear sign of her ability. The document gives a picture of traditional rural society only a few years before William was born, and is thoroughly Catholic with its appeal to the Angels and the Virgin Mary ‘and all the blessed company of saints’. Henry VIII’s Reformation had so far touched this part of Warwickshire only lightly. In keeping with most of her class and neighbours, Mary Arden would have been brought up in a highly ritualized, old-fashioned English country Catholicism.

Attached to the will is an inventory of Robert’s goods, which enables us to imagine the house as it was furnished in the year before Mary married. The list of possessions reflects the changing world of the Tudor lower middle classes and includes eight painted tapestries, tables, chairs, benches, a cupboard, beds and bed linen. No plate is mentioned: as was customary in some places even until the nineteenth century, the Ardens would have eaten out of wooden bowls. In the kitchen were pots, skillets, a frying pan, a cauldron and pewter candlesticks; and there was ‘bacon in the roof’. In the outhouse Robert kept a good kit of carpentry tools – he was obviously a skilled woodworker. The barn housed a cart, harness and gear, a heavy plough and an eight-ox team of the kind that had been traditional since pre-Conquest days. The inventory also lists cattle, sheep, pigs, horses, beehives and sown wheat in the fields. Quite an extensive holding, it suggests a well-off middle-class landowner of the sixteenth century who would have employed both permanent workers and seasonal labourers. Although not rich enough to possess woven tapestries, the family was still able to afford painted cloths of the ki

nd Shakespeare would later describe in his works (Falstaff talks of being ‘frightened by a painted cloth’, referring to cloths with religious themes; in The Rape of Lucrece the poet mentions a painted cloth depicting the story of the siege of Troy).

Shakespeare’s grandfather’s inventory is fascinating because it reveals the material culture of the class out of which William came; it anchors us in his reality as a child. Not only the cloths on the wall, with their frightening and fascinating images, but the skillets, iron crows, pails, mattocks, cauldrons, augers, querns, handsaws, joint stools, cupboards, benches, bolsters, pillows and diapers listed in the inventory of his mother’s home are all words used in his plays. This house, with its furnishings, represents the world into which William would be born: solid, down-to-earth, practical.

THE ACCESSION OF ELIZABETH

After her father’s death Mary became a woman of property with her acres in Wilmcote and her portion in Snitterfield. She married John Shakespeare a few months later in early 1557, when she was at least seventeen and maybe even in her early twenties. The wedding is likely to have been solemnized at the parish church of Wilmcote at Aston Cantlow; and, given the date and the history of the families, it would have been a Catholic service followed by a mass. Then the couple moved into a new house in Henley Street, where they could look forward to a prosperous middle-class provincial lifestyle, with some pewter on the table, good linen in the cupboard, hangings on the wall, a table laid for guests, and a servant or two. In Queen Mary’s Stratford this was what it meant to have standing in the world.

But their world was about to change. Scarcely more than a year after John and Mary’s marriage, the queen died. In her short reign she had reinstated Catholicism as the national religion and bitterly persecuted Protestants, some of whom had been burnt at the stake in nearby Coventry. On 17 November 1558 Mary’s half-sister Elizabeth came to the throne. The daughter of Henry VIII by Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth instituted a return to the stalled Protestant Reformation of her father and her half-brother Edward VI. With the nation already in a state of deep anxiety over recent changes of rulers and religion, people braced themselves for the next phase in the war for English hearts and minds.

Like all parishes, Stratford celebrated the coming of a new ruler with the traditional rituals. The following Sunday, the first in Advent, the leading townsmen, including John Shakespeare, would have processed to church to proclaim the new queen and to pray for a happy and prosperous reign; but they would have recited ‘Our Father’ and ‘Hail Mary’ for her prosperity, sung with the Latin litanies and collects for a Catholic ruler. The mood of the congregation that day was probably nervous. Some neighbours and friends were Protestants, and one or two perhaps leaned towards Puritanism; but most were old Catholics, and traditionalists in the town (although they might have been horrified by the Coventry burnings) would have agreed with the churchwardens in one Berkshire parish that under Henry and Edward ‘all godly ceremonies and good uses were taken out of the church … all goodness and godliness despised and in manner banished … [when] devout religion and honest behaviour of men was accounted and taken for superstition and hypocrisy’. For them, Mary’s reign had been a time when ‘the church was restored and comforted again’. In this part of Warwickshire many would have agreed with that. Even twenty-five years later a Rowington villager spoke on behalf of his community when he said of the Old Faith, ‘This is our religion here.’

So what did the future hold? After mass, across England the parishes rang bells and lit bonfires at church gates, with a dole of cheese, bread and beer for the poor. But the fires of Elizabeth’s accession ceremonies were to be the funeral rites of Catholic England. A year later in July 1559, the government brought in measures ‘to plant true religion’. What this meant was the suppression of all Catholic ceremonial and imagery: the destruction of altars and images, rood lofts, wall paintings, stained glass and ritual vestments. Parish priests (who were still mainly of Queen Mary’s Church) were instructed to adopt new rituals, a new prayerbook and the authorized Protestant Bible. In many parts of the country churchwardens were required to prepare a document containing an inventory of all the ‘church goods’, together with ‘all the names of all the houselling people in the parish and the names of all them that were buried there since midsummer and was twelvemonth Christened and wedded’. ‘Houselling’ – a word Shakespeare puts into the mouth of Old Hamlet’s ghost – designated those who took Catholic communion.

So the process was beginning by which the government would gradually cast a net round all the adherents to the Old Faith. A battle had begun between power and conscience which would take the best part of half a century to resolve itself. Broadly speaking, historians now see the process in four phases: in the first dozen or so years of Elizabeth’s reign an uneasy equilibrium was maintained; then, from around the time Shakespeare started school in 1571, the storm gathered; not long after he left school in 1580 the crisis began with the missions of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, and the ensuing repression; and finally, from the beginning of the 1590s, the establishment gained the ascendancy. This period of cultural revolution spanned most of Shakespeare’s lifetime and is crucial to an understanding of his mind and thought.

TWO FUNERALS AND A CHRISTENING

Although she purged the universities, the powerhouses of ideology, early in her reign, Elizabeth did not at first set out to persecute her subjects. She was a sincere Protestant, but not a zealous reformer and had no desire, as she put it, to ‘open windows into men’s souls’. This laissez-faire attitude must for a time have kept most ordinary people happy. For who could tell, at this moment, what they might be called on to believe in the future? So in Stratford they didn’t rock the boat but just got on with their lives. Under the new queen the town was still run by the old regime, and John Shakespeare rose fast to become borough treasurer, a member of the town corporation. He was a man who could be trusted to assess a situation: the property of a deceased neighbour, the standard of workmanship on corporation property, or the quality of brewers’ ale.

Meanwhile, in his private life John was hoping to become a father. Mary had got pregnant quickly but their first child, Joan, born in September 1558 and baptized as a Catholic, died in infancy. As was the custom, the name would be used again. A second daughter, Margaret, was born in December 1562 but died within five months. Infant mortality was high in those days: in the big cities nearly a third died before their first birthday and even in the kinder air of Stratford, child deaths reached the same grim level in the 1560s. Another daughter, Anne, would die at the age of seven.

The death of their first two children must have hit the parents hard, but Mary conceived again in the summer of 1563. It would be interesting to know if they resorted to any particular prayers or rituals to safeguard this special baby. There is some evidence that John’s patron saint was Winifrid of Holywell, whose shrine was a place of pilgrimage for old Warwickshire families like the Throgmortons and the Fortescues of Alveston. The intercession of such accessible female saints, who were painted on the nave in the guild chapel in Stratford, was often sought in matters of childbirth.

John and Mary’s first son, William, was born in late April 1564, and within a day or two was christened in Stratford parish church by John Bretchgirdle, a humanist scholar with Catholic sympathies, whose curate had drawn up Catholic wills and who had performed old-style baptisms for parishioners. The date of the baptism was 26 April and the birth date is traditionally held to be the 23rd. But this is only supposition. Usually children were baptised within five days of birth, which means he could have been born as early as the 20th. In traditional belief, which would largely die away over the next couple of generations, it was important to have a baby baptized as soon as possible: being born with original sin, a child who died unbaptized was believed to go not to heaven but into limbo. The boy’s name has no more significance than any other: he was presumably named after his godfather who may have been William Smith, a haberdasher

and Henley Street neighbour who headed a very aspirant family – all five of his sons were literate, and one went to university. The vicar’s entry in the register, copied by a slightly later hand, says simply: ‘26 April William son of John Shakespeare.’

CHAPTER TWO

A CHILD OF STATE

IT WAS A hot summer in 1564. Under Clopton Bridge the strong current of the river Avon eddied around the stone piles where the children liked to swim to cool off; at lowest water they could stand on the old Roman ford which gave the town its name. The tall spire of Holy Trinity Church peeped over rows of elms – there were said to be 1000 of them – which gave shade to the lanes that led into the town. Indeed, the countryside came right to the town edge: fields butted on to the back gardens along the Gild Pits behind the Shakespeares’ house in Henley Street, and a stream, the Meeres brook, ran across the road and along a gulley through the market place.

But even in small-town Tudor England such as this, a ‘Great Rebuilding’ of domestic housing was under way, accompanied for the middle class by a significant rise in the standard of living. In the old world into which Shakespeare’s parents had been born, each family had lived in a communal hall where they all slept on straw pallets with ‘a good round log under the head’, as one contemporary observed; pillows were just ‘for women in childbed’. But old habits were changing: privacy was now much sought after and possessions were becoming a mark of status. For those who were old enough to remember the days of Henry VIII, ‘three things are marvellously altered in England within their sound remembrance’, wrote William Harrison in 1587: ‘the multitude of chimneys’ needed for private rooms, the accumulation of furniture and possessions in houses, and the variety that middle-class people now expected on the table.

The Story of India

The Story of India Stolen Children

Stolen Children In Search of the First Civilizations

In Search of the First Civilizations The Murder House

The Murder House A Room Full of Killers

A Room Full of Killers In Search of the Dark Ages

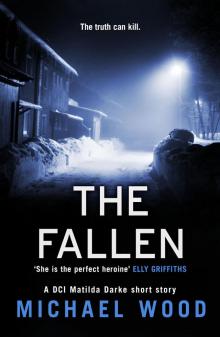

In Search of the Dark Ages The Fallen

The Fallen Time Is Running Out

Time Is Running Out A South Indian Journey

A South Indian Journey In Search of Shakespeare

In Search of Shakespeare The Hangman's Hold

The Hangman's Hold For Reasons Unknown

For Reasons Unknown Outside Looking In

Outside Looking In