- Home

- Michael Wood

In Search of the Dark Ages Page 4

In Search of the Dark Ages Read online

Page 4

Boudica poisoned herself. Dio adds that she was buried secretly with great honour, but where this took place we have no means of knowing. The discovery of her burial place would cause an archaeological sensation, but it is unlikely. To us she must remain an enigma, more alien and less comprehensible than the Romans who hated and destroyed her.

THE CLEAR-UP

For a time the future of the Roman province of Britain hung on a thread. In a few months the revolt had spread from Norfolk to Somerset. Now the Roman military establishment would make sure that it never happened again.

Ten miles from the battlefield a great supply base was set up at a place called the Lunt, near Coventry, as the first stage in the Roman army’s campaign of revenge. The most striking feature of the fort there was a gyrus, a circular arena with a wooden fence for breaking in horses. It has been suggested that this unique feature could have been part of a collecting point for Iceni horses after the battle. Other buildings included a large granary, stable-blocks and equipment sheds, barracks, foundries where cavalry equipment could be manufactured, and an exceptionally large headquarters block which indicates the presence of a top-ranking officer. The fort was short lived. It was begun around AD 60 because of the rebellion, when the new fort was suddenly constructed very hurriedly. This fort was very extensive indeed, for remains have been uncovered well beyond the 4½-acre site which can be seen reconstructed today. In fact the outer defences of the Boudican period fort have not yet been located, so it may have extended over the whole of the Lunt plateau in the loop of the river Sowe, comprising at least 25 acres.

When the immediate military situation in the Midlands was resolved, and the bulk of the Roman forces moved into Iceni territory, the huge first camp was replaced by a more compact 4½-acre fort centring on the gyrus and the HQ building. This smaller version was built in the early sixties and abandoned and dismantled around AD 80 by an army demolition squad. A fascinating insight into the mentality of the Roman military hierarchy in Britain was provided by the discovery that the fort had been reoccupied in the late third century at the period when the Saxon Shore forts were being constructed by the Romans against Anglo-Saxon invaders. It seems that when the Roman army decommissioned the fort in AD 80, they maintained ownership of the site. They had learned their lesson from Boudica. Her rebellion had been fanned by native resentment of appropriation of their land for military use. So for nearly 200 years the Lunt (and others in all probability) were kept as open spare sites for forts, ready for any future trouble.

BACK INTO ICENI LAND

So we can imagine the Lunt plateau in the aftermath of Boudica’s revolt as a scene of extraordinary activity: a vast military encampment, the slopes all around covered with stockades for horses and dumps of grain; smithies furiously producing horseshoes, the coming and going of cavalry detachments; a constant stream of Iceni horses being broken in on the arena of the gyrus; Roman reinforcements training along the river Sowe, the slopes and the almost vertical face of the escarpment. All this would be prior to Suetonius’ drive into Iceni territory. The whole army was kept ‘under canvas’ (ie, in tents in the field) for the winter in order to finish the war. Two thousand regular troops were transferred from Germany with eight auxiliary infantry battalions and a thousand cavalry: a measure of Roman losses in the campaign. Then Suetonius pushed into Iceni and Trinovantian land, establishing new winter quarters from which he could ravage hostile or wavering tribes with fire and sword. ‘But the enemy’s worst affliction was famine,’ says Tacitus, ‘for they had neglected sowing their fields and brought everyone available into the army intending to seize our supplies.’

As the army tightened its grip on the Iceni, a chain of forts was constructed across East Anglia, including ones at Saham Toney, at Warham, at the Gosbecks, and probably at Caistor-by-Norwich. After the fire and sword came a second stage. The Iceni were to be Romanised through and through in order to enjoy the full benefits of Roman civilisation. The new generations who grew up after AD 60 would grow up in a Roman world.

Within a few years of the revolt, one branch of the Iceni was moved from its tribal centre and settled in a new city planned along the lines of the Roman model at Caistor-by-Norwich. It was to be called Venta Icenorum, the market town of the Iceni. It was never a great success, although it was later dignified with a forum, baths and public works. The site laid out after the revolt was small compared with other tribal capitals, but it still proved too big; many plots were never taken up and it remained half empty for a long time before it contracted to the present walled city in the late first century. After the Fall of Rome the city was never reoccupied and its walls still stand today, up to twenty feet high in places, under their earth banks. The lines of its streets were still visible from the air in the days when its great central rectangle was laid out to crops.

And what of the Iceni themselves? They remain an enigma. We know little of them before Boudica and even less after. Almost a generation of men must have been lost in the war and the famine, devastation and slavery that followed their defeat. The royal family and leading men will have been ruthlessly purged. The peasants lived on – perhaps the imposition of Roman rule meant little to them – and after the Fall of Rome we lose sight of them. But it may be that the British-speaking fen dwellers, the itinerant horse dealers and thieves who lived on the fringe of Norfolk society for centuries afterwards were the last of the Iceni. Let the imagination play and it is not difficult to see in the dark Celtic-looking faces you see today in Norwich streets the descendants of those people. As for Boudica herself no personal trace has ever been found. The costly tomb which Dio Cassius says was built for her is an intriguing but remote possibility. Her memorial lies in the pages of the historians of her bitterest enemies.

TWO

KING ARTHUR

Then Arthur fought against them in those days with the kings of the Britons, and it was he who led their battles.

Nennius History of the Britons

THERE IS NO Myth in British History, and few in the world, to match the story of King Arthur: the knights of the Round Table, Guinevere, Lancelot, the quest for the Holy Grail. Since the Middle Ages these tales have exerted their fascination and continue to do so today, particularly in a declining Britain where the myth of a golden age has obvious attractions. But beneath the legend lie the real events of the fifth century; the period of the fall of the Roman Empire. This time remains the darkest, the least documented, in British history. Yet through the shadows modern historians think they have distinguished a remote war leader, a real-life British hero who is said to have died around 500, and whose fame, it is thought, grew from successful battles against the Anglo-Saxon invaders who poured into Britain from northern Europe and Scandinavia after the fall of Rome, the ancestors of today’s English. But are the historians right?

In spite of their obscurity the years following 500 were some of the most important in the 2000 years of recorded British history. It was then that the key racial and linguistic alignments of Britain were defined. The Celtic inhabitants of Britain were driven into Cornwall, Wales, Strathclyde and Scotland by the Anglo-Saxon newcomers who settled in the east and south in what was later to be called England. The dispossession of the Celtic people of Britain by the Anglo-Saxon invaders was the subject of a huge literature in the Middle Ages, and in Arthur it had its greatest hero.

The purpose of this chapter is to look at the way in which Roman civilisation in Britain came to an end, and to see what justification there is to link a historical Arthur to these events. Go into any bookshop today and you will find yourself in no doubt that he existed. A mass of Arthurian books is available, from reputable academic works to theories from the lunatic fringe. In them Arthur emerges as everything from cult hero to guerrilla generalissimo, Dark Age Superman to Dark Age Che Guevara. They remind us that every age makes of Arthur what it will. In the eighteenth century Gibbon contented himself with noting that ‘the severity of the present age is inclined to question the exist

ence of Arthur’ and wisely avoided conjecturing a career for him. Macaulay in the early nineteenth century thought him ‘no more worthy of belief than Hercules’. It has been the twentieth century which has sought to corroborate the details of the myth and find a historical Arthur. The Victorians perhaps paved the way for this. Books like Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, which were based on the legend, had a fantastic emotional impact on the late Victorians, with its stress on chivalry, heroism, and nationalism, and its dark strain of sexual jealousy and betrayal. All this appealed to the Victorians’ nostalgia for a lost golden age.

But Victorian England was also the era of the birth of scientific archaeology. Remarkable discoveries were made in Greece, Crete, and Turkey by the German, Heinrich Schliemann, which were thought to have proved that the Homeric legends were ‘true’, that Agamemnon and Achilles had existed and that Troy was sacked by the Greeks just as had been described in Homer’s poems. We now know that Schliemann was wrong in most of his conjectures about Troy and Mycenae, but it is perhaps not surprising that British scholars of the early part of this century, brought up in this intellectual milieu, should have been the first to try to reconcile the legend of Arthur with historical fact, to work out a rational account of the Arthurian story and to suggest that behind the tale of Arthur and his knights lay a historical armoured cavalry leader with a brief to drive back the Anglo-Saxon hordes as Roman power in Britain ebbed.

As at Mycenae and Troy, finds of the right period have been pressed into service. Since the Second World War historians have not only gone back to Glastonbury and Cadbury and ‘found’ Avalon and Camelot, but have built up a detailed history of Arthur’s empire and its political ideologies. We shall look at the sources for these conjectures later. Let us simply note now that it is a natural impulse for societies to construct a golden age retrospectively, and for the most part such speculations are no more than that. An example of this was the discovery of ‘Arthur’s tomb’ at Glastonbury. In the mid twelfth century Geoffrey of Monmouth’s fanciful book, History of the Britons, fired the imagination of the credulous intelligentsia of the time. In 1191, six years after the destruction of their abbey by fire, and with their restoration fund badly needing a boost, the monks of Glastonbury dug secretly in their old cemetery and ‘discovered’ the remains of a large man buried in a tree trunk. This, they claimed, was King Arthur himself, and they produced a forged inscription to prove it. Eyewitnesses had not mentioned a woman, but it was soon said that Guinevere had also been found. Given the medieval propensity to manufacture relics, no disinterested observer would think this find had any more relation to King Arthur than the subsequent discoveries in the same place of the sword Excalibur and the grave of Joseph of Arimathea. It is interesting to note that the great twelfth-century expert on Glastonbury, William of Malmesbury, who wrote an official history of the monastery just before Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote his book, specifically denies that the burial place of Arthur was known. Nevertheless the 1191 discovery has been accepted as the grave of King Arthur by a number of scholars in recent years.

There is even more doubt about the Arthurian associations with such tourist spots as Tintagel, Amesbury, Winchester and Cadbury. In the main they are the inventions of twelfth-century romantic poets. If we wish to uncover real events behind the stories we must do as William of Malmesbury enjoined us all those years ago: ‘Throw out such dubious stuff and gird ourselves for a factual narrative.’ The question is, what happened in Britain at the fall of the Roman empire? Bound up with that, there is a second question: did there exist at this time a war leader called Arthur? In much of this chapter we will be examining the historical background to the late fifth century. It is only when we understand the nature of that time that we will be in a position to evaluate the evidence for Arthur’s existence.

A WORLD IN DECLINE?

Portchester on the south coast of England. This massive Roman fortress, the best preserved in northern Europe, was one of a dozen built around the year 300 to defend Britain against the incursions of Anglo-Saxon invaders. The society it was to protect was already under stress, with class divisions, a decline in trade and depopulation of towns, a falling birthrate, high inflation, the gradual collapse of a money economy, and the growth of great private rural estates.

In 410 came the end of 350 years of Roman colonial rule; a period as long as that in which the Portuguese ruled over Angola, longer than the British supremacy in India. The Romans did not simply abandon England and sail back to Italy. Their armies had been gradually withdrawing in the preceding years, and before that there were several periods when the Britons had elected their own emperors and cut their links with the Roman government on the continent. What happened in 410 was a formal severance of responsibility for defence. But Britain had been a Roman province for so long that the Roman influence remained long after the Roman departure. The problem of how long Romanitas continued here is one of the cruxes of early English history and archaeology. Historians now recognise that the western provinces of the Roman empire remained a recognisably sub-Roman civilisation for centuries under the barbarian Germanic tribes who took over.

The first few years of the fifth century were critical for the western Roman empire, threatened on all sides by barbarian peoples breaking through the frontiers. One barbarian chief, Alaric, King of the Visigoths, appeared in Italy in 401 and besieged Rome in 408, finally entering it in 410. Other Germanic peoples, the Vandals, Suevi and Burgundians, struck into Gaul in 407. It was to meet this challenge that the Romans were forced to withdraw troops from Britain. The Britons themselves were under increasing threat from Scottish, Pictish and Anglo-Saxon raiders, and with no help forthcoming from Rome, elected their own leaders, one of whom, Constantine, held power from 407 to 411 and led troops into Gaul against the Roman government there. According to the Gallic Chronicle, Britain, deprived of fighting men, then suffered a large-scale invasion in 408. ‘The provinces of Britain laid waste by the Saxons: in Gaul the barbarians prevailed and Roman power diminished.’ What happened next is the subject of argument. The general view is that though their leader Constantine was fighting in Gaul and called himself an emperor, the Britons did not consider that they had ceased to be part of the Roman Empire. In 410 they appealed for help to Emperor Honorius in Rome but he could do nothing except order the local communities to arrange for their own defence. Rome had troubles of its own: in the same year it was sacked by the Visigoth Alaric.

A different perspective can be seen in the works of the late fifth-century Byzantine writer Zosimus, which explains how the Britons were able to resist the Anglo-Saxon invaders successfully. According to Zosimus it was the Saxon ravages (presumably culminating in the 408 attack) which forced the inhabitants of Britain to secede from the Roman Empire in a kind of UDI, and become once again ‘another world’. They organised their own defence, took up arms, and ‘braving every danger freed their cities from the invading barbarians’.

Some historians have suggested that this revolt went hand in hand with a social revolution, a peasant revolt like the Bacaudae in Gaul, and that the peasantry successfully opposed the Romano-British upper class and defeated the Anglo-Saxons. The appeal to Honorius in Rome would then have been a last plea from the threatened landed class. It has even been proposed that this revolution went hand in hand with a radical religious movement, Pelagianism, a new kind of puritanism born out of a time of stress. However, it is now thought that this theory is unlikely to be true and that there was no movement for social reform. In fact it is probable that the people who reorganised Britain’s defence in the early fifth century were the Romanised urban upper classes, the curiales, in the areas where town life still functioned.

Two contemporary sources throw some light on this dark period of British history: a biography of St Germanus and St Patrick’s Confessions. In 429 St Germanus came to the island as an agent of the Catholic Church in Rome to combat the spread of the heretical Pelagianism, and though there were serious incursions in the s

outh by Saxon and Pictish pirates, according to the biography, organised Roman town life still continued. Local magistrates were still in charge in the cities and there was obviously nothing unusual in a bishop from the continent travelling through the province to correct ecclesiastical observance. By the time of St Germanus’ second visit in 447 the island was still holding out against the Saxons, if the author of the saint’s biography is to be believed: writing in the 480s (which was precisely the supposed period of the Arthurian wars) he speaks of Britain as essentially Roman in administration and orthodox in worship, and most remarkably, ‘a very wealthy island’.

ST PATRICK

The most interesting source for this period is the Confessions of St Patrick. Patrick, the patron saint of the Irish, was in fact a mainland Roman Briton taken into slavery in Ireland at the age of sixteen in one of the raids around 400; one of thousands seized by pirates. His father owned a small villa in the west (perhaps in the region of Carlisle), was a local town councillor, and a church deacon. Escaping from captivity in Ireland the young Patrick took passage on a trading ship to Gaul, which was then being devastated by far-reaching barbarian raids. The key point about Patrick’s narrative is that when he returned to Britain in c. 415, five years after the Romans had left Britain, there is no suggestion of anarchy, and when he wrote his account in the middle years of the century the imperial Roman system of local government was intact. The local town councils, for example, were still responsible for raising taxes for the government. It was still a world where professional rhetoricians could earn a living as they could in Rome; a world where a letter writer could address the British dynasty of Strathclyde as ‘fellow citizens’. We can therefore assume the continuation of a feeling of identity with Rome in the Romano-British ruling class, the senatorial aristocracy and the local landowners. This is the kind of background we would expect for an historical Arthur.

The Story of India

The Story of India Stolen Children

Stolen Children In Search of the First Civilizations

In Search of the First Civilizations The Murder House

The Murder House A Room Full of Killers

A Room Full of Killers In Search of the Dark Ages

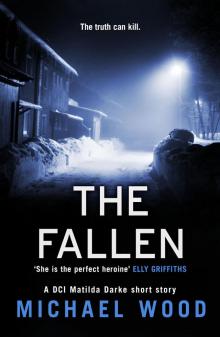

In Search of the Dark Ages The Fallen

The Fallen Time Is Running Out

Time Is Running Out A South Indian Journey

A South Indian Journey In Search of Shakespeare

In Search of Shakespeare The Hangman's Hold

The Hangman's Hold For Reasons Unknown

For Reasons Unknown Outside Looking In

Outside Looking In