- Home

- Michael Wood

In Search of Shakespeare Page 6

In Search of Shakespeare Read online

Page 6

Education was chiefly in the language of authority, church and the law: Latin. Years later, in a back-handed compliment, Ben Jonson said Shakespeare had ‘small Latin and less Greek’. This is often quoted as if to dismiss Shakespeare’s education, but Jonson’s remark needs to be taken in perspective. Jonson himself was a very good Latin scholar. What would be ‘small Latin’ in his day was much more than is mastered by many a classics graduate now. Even in country grammar schools from Devon to Cumbria, boys were expected to ‘speak Latin purely and readily’. The quotes in Shakespeare’s plays show that he started with the nationally prescribed text Lily’s Latin Grammar (which he sends up in The Merry Wives of Windsor), then books of ‘Sentences’, before moving on to Dialogues and, at eight or nine, to full texts of writers such as Ovid.

As Jonson tells us, Shakespeare also knew some Greek; this was indeed part of the curriculum. As far away as Bangor in Wales in 1568, it was declared that ‘nothing shall be taught in the said school but only grammar and authors on the Latin and Greek tongues’. At Harrow in Shakespeares day the boys started Greek grammar in the fourth year. If the regime at Stratford was similar, he might have been able to follow, with a crib, a Greek text such as Aesop’s Fables.

The end product was a poet who could and did sit down and read a book or play in Latin – although, like most people then and now, he would have preferred a translation for speed. Late in his career, in The Tempest, he gives the correct translation of a word in Ovid omitted in the English version by Arthur Golding.

If all this is a surprise, remember that Tudor England was probably the most literate society that had yet existed in history; Thomas More, in his Apologye, estimated basic literacy to be 60 per cent. This may seem unbelievable in a country where half the population was living below the poverty line. But England’s first literacy revolution, in the thirteenth century, had brought basic reading down into the peasantry for simple mortgages, legal cases and prayers. In land documents relating to the medieval ancestors of the Tudor yeoman class, the use of limited literacy with a personal seal is commonplace as early as the 1200s. So the dramatic Tudor expansion of literacy was the culmination of a long period of growth. By the 1550s, many grammar schools had sprung up all over England, and 160 more would be opened during Elizabeth’s reign. Some were the foundations of rich philanthropic benefactors; but many, like the one in Stratford, were the direct descendants of the guild school. In the generation educated as a result of this great burst of grammar school foundations in the 1560s and 1570s, the literacy figures shot up. Literacy was not limited to boys – we know that girls attended petty school in Stratford – but from the age of seven, school seems to have been confined to boys, except in wealthy or noble families. Shakespeare, then, was a child of the English Renaissance, who was lucky to be born in a privileged generation.

ROTE LEARNING, DEBATE AND DEFERENCE

It started at the crack of dawn. A grammar school boy got up at five, said his morning prayers, then departed for school at six in summer, seven in winter. Schoolchildren took only a small breakfast: the main meals in the Tudor age were dinner (at midday) and supper (at six o’clock for a tradesman like John, eight for farmers like his brother in Snitterfield who worked a longer day). In the schoolroom there were two classes at opposite ends of the room, sometimes separated by a screen. The younger boys were supervised by the usher, the older ones by the master; those young ones who needed to catch up may have had special writing lessons with an outside tutor. In winter, when the weather was cold, the schoolroom was warmed by a brazier. Parents were expected to provide their child with ink, paper, quill pens and wax candles.

The regime was strict: boys learned by rote, and beating was the norm. Later, in his plays, Shakespeare paints a picture of lessons as a grind; but in As You Like It he talks of the schoolboy going to school with his ‘shiny morning face’, recalling chill, dark Stratford mornings and the unquenchable optimism of childhood.

Shakespeare was the product of a memorizing culture in which huge chunks of literature were learned off by heart. Today we no longer live in such a culture, but learning by rote offers many rewards, not least a sense of poetry, rhythm and refinement – a feel for heightened language. It forms habits of mind too: what they called the ‘art of memory’ was an invaluable tool when it came to composing speeches. Teachers also used classroom debate to improve Latin and develop rhetorical skills. The Harrow school statutes of 1580 required every schoolmaster there to hear debates for an hour each day with the third, fourth and fifth forms (that is, those aged about nine to eleven). Each boy in turn stood in front of the class and defended a proposition, for example, whether Brutus was right to assassinate Caesar. (The school textbook on composition, Thomas Wilson’s Art of Rhetorique, which urged the importance of writing about English matters in English, also suggests that boys could make comparisons from English history, for instance between Richard III and Henry VI.) All this would come out later in Shakespeare’s plays: in The Merry Wives of Windsor he sends up a Latin class with a Welsh headmaster (his own Mr Jenkins?) and quotes the textbook that bored him and his classmates to death, Lily’s Grammar, with terrible jokes about focatives, genetivos, horums and harums. Schoolboy humour never changes.

Politeness and deference were drummed into pupils by Elizabethan schoolmasters: ‘to thy Parents duty yield, Unto all Men be courteous, and mannerly in town and field’. This reverence for parents is expressed in a letter of the time, written in Latin as a school exercise by an eleven-year-old Stratford schoolboy, Richard Quiney, to his father, a family friend of the Shakespeares: ‘Patri suo amantissimo Magistro Richardo Quinye,’ it begins; ‘With all respect – but even more with filial affection towards you, my father, I thank you for all the kindnesses which you have bestowed upon me …’ After a dozen lines of formal Latin, culled from the style manual of Cicero’s letters, the boy’s missive ends (in translation): ‘Although I could never repay your kindnesses, I wish you all prosperity from my heart of hearts … Your little son most obedient to you Richard Quiney.’

Filial devotion and civic-mindedness: such was the style of Tudor education. The letter shows what an eleven-year-old Stratford grocer’s son could do after four years at grammar school; William would no doubt have had to write the same sort of model letter to his own proud father. Such sentiments of politeness are expressed in the plays time and again: they recall descriptions of ‘gentle’ Shakespeare’s character in later life, his ‘civil and honest’ demeanour, his ‘facetious grace’. That was what a good provincial school education gave you.

SCHOOLMASTERS OF THE OLD FAITH

The room where he was taught is still above the guildhall, still used for teaching, and the boys still call it ‘Big School’. It is an atmospheric place with rows of eighteenth-century desks covered with carved initials and doodles blackened with age. On the ground floor fragments of Tudor wall paintings are still visible on the lath and plaster wall of the old guildhall; this is where the corporation met and where travelling players performed throughout Shakespeare’s childhood; here in 1586 the packed townspeople almost lifted the roof off when the greatest stand-up comic of the age, Richard Tarlton, stuck his head through the curtain and began to pull the most famous face in English drama.

Stratford council paid their schoolmaster £20 a year and provided a house and removal expenses. It was a good salary for the time – better than that of the headmaster of Eton, although at Eton there were more perks. The names of the incumbents at Stratford going back to the refounding of 1553 are painted on a wooden board in Big School. They were good Oxford graduates, selected by the senior men of the corporation, and in the town book is the wording of the oath sworn by every new master to be a ‘trusty and wellbeloved bachelor of arts … lawful and honest man learned in grammar and in the law of god’ (the old connection made by medieval educators). He was ‘henceforth diligently to employ himself with such godly wisdom and learning as God hath and shall endue him with: to learn and teach

in the said grammar school all such scholars and children as shall come together to learn godly learning and wisdom being fit for the grammar school or at the least-wise entered or ready to enter into the accidence and principles of grammar’.

That contract demonstrates the importance of the religious dimension in Tudor education. The statutes of Tudor schools all included instruction in the chief points of faith, the aim being to produce good conforming members of the Protestant state; and in the government’s eyes Shakespeare’s was the target generation. He would already have known the Lord’s Prayer, the Creed and the Catechism, and at school he would have spent considerable time on the main articles of the Protestant faith. But in the early years of Elizabeth’s reign such things were not cut and dried, even at school: in Stratford at least four of the six teachers in Shakespeare’s time had Catholic leanings. Two of them came from Oxford colleges with especially strong connections: St John’s (the Jesuit martyr Edmund Campion’s college) and Brasenose (known until recently for its links with Lancashire Catholicism). Of these masters, Simon Hunt would have taught William in his upper school from about 1573. Hunt was a private Catholic, or at least Catholic in sympathies, who in 1575 retired to the seminary at Douai and became a Jesuit.

Nor was this situation unique to Stratford, as the government was well aware. In June 1580, not long after Shakespeare had left school, Elizabeth’s Privy Council sent a letter to all dioceses detailing their continuing concerns about Catholic influences in education and urging the bishops ‘to have regard to the daily corruption grown by schoolmasters both public and private in the teaching and instructing of youth’. In April 1582 this would stretch to intervention on the kind of books used at school, especially ‘the poets as are commonly read and taught in grammar schools’. The Privy Council recommended a new verse book of Protestant history with an appendix on the ‘peaceable government of the Queenes Majesty’ in place of ‘some of the heathen poets now … publicly read and taught by schoolmasters’.

In the light of such evidence, the presence of so many sympathizers with the Old Faith at Stratford grammar school in the 1570s is interesting. The corporation had vetted and hired these teachers for their ‘learning and godliness’, and they clearly preferred to hire their own kind of teacher. Simon Hunt was recruited a year or so after the Northern Rebellion, when John Shakespeare was deputy bailiff. Was it a deliberate political act by an old-fashioned corporation? The times, after all, could still change.

STREET THEATRE AND PLAYS IN THE GUILDHALL

But there was more to life for a boy than religion. Every year the streets of Stratford hosted a pageant of St George and the Dragon (the sword that dispatched the beast is still kept in the town hall). In small-town Warwickshire it was one of many shows, pageants and folk plays based on local history and legends such as Guy of Warwick, the Dunsmore Cow and the Boar of Callidon. The Hoke Day pageant in Coventry, for instance, celebrated battles in which the English had defeated the Danes, ending with the invaders ‘led captive by our English women’; typically, it was attended by much junketing and brawling by rowdy young men. Shakespeare must have seen this sort of entertainment from very early in his life. Performance, acting and declaiming were at the heart of English culture in those times: from a king to a plain alderman, you had to be able to speak up in public and argue a good case. And great performances of the day, whether on the stage, in the pulpit or on the scaffold, were held up as models of style as well as of courage, constancy or virtue.

Puritans, of course, viewed such fripperies as stage and street theatre with distaste. For them, actors were ‘schoolmasters of vice and provocations to corruption’, and many wanted to protect the young and impressionable by banning plays altogether: ‘What great care should be had in the education of children,’ wrote one old fogey, ‘to keep them from seeing spectacles of ill examples and hearing of lascivious or scurrilous words, for that their young memories are like fair writing-tables.’ Such censorship would come, but not in Shakespeare’s life. Yet again, he was lucky in his time.

Even before he went to school, Shakespeare had surely already encountered the magic of the theatre. In 1569 the town accounts record that Shakespeare’s father, as mayor, welcomed players to Stratford and paid donations from the borough purse:

Item payd to the Quenes Pleyers ix s

Item to the Erie of Worcesters Pleers xii d

A contemporary, Robert Willis, born in the same year as Shakespeare, describes a similar show in Gloucester:

As in other like corporations, when players of interludes come to town they first attend the Mayor to inform him what nobleman’s servants they are, and so to get licence for their public playing; and if the Mayor likes the actors … he appoints them to play their first play before himself and the aldermen and the common council; and that is called the Mayor’s Play, where every one that will goes in without money, the Mayor giving the players a reward as he thinks fit to show respect unto them. My father took me with him, and made me stand between his legs, as he sat upon one of the benches, where we saw and heard very well. This sight took such an impression in me that when I came towards man’s estate it was as fresh in my memory as if I had seen it newly acted.

‘BEAR WITNESS … THAT THERE ARE NO GODS’

Once Shakespeare went to school, plays and acting, which were regarded as an important element in the education process, would have been a regular part of his experience. Indeed, early in the Reformation, in the 1550s, educators wrote didactic school plays such as Ralph Roister Doister, which taught a moral lesson and included patriotic songs and prayers for the queen.

At school Shakespeare also did plays in Latin. This is perhaps where he first encountered the Roman comedies of Plautus, which inspired his own comedies of mistaken identity, The Comedy of Errors and Twelfth Night. More important still was the Roman dramatist Seneca, a vast presence who shaped the imagination of Renaissance Europe. By now Greek drama was well known among European intellectuals in Latin versions such as Erasmus’s translations of Euripides, but, writing as they did in an age of despotism, the Elizabethan dramatists felt their greatest affinity was with Seneca, the philosopher-poet at Nero’s court who died by suicide – the fate of a writer in an age of tyranny. Seneca had been translated into English in the 1550s, but was still studied in Latin at school. And to schoolboys his work must have been shocking: a theatre of cruelty, whose terrible images of human beings brought to the ultimate point of endurance matched the judicial atrocities performed as exemplary and theatrical punishments on the public stage of Elizabethan England. The great Greek dramatists measured human suffering in the balance of divine justice, but Seneca rejected any evidence of such justice. Indeed, to him the gods were hardly more than names for the inscrutable and remorseless forces of history and the self-destructive urges of humanity itself: ‘Go on through the lofty spaces of high heaven,’ cries Seneca’s Jason to Medea. ‘And bear witness where you ride that there are no gods.’ In his art, as in his life, Seneca placed in opposition to these blind malignant forces the power of rationality, the Stoic affirmation of a kingdom of the mind, unshaken by tyranny and unmoved by horrors:

Not riches makes a king …

A king is he that hath laid fear aside,

And all affects that in the breast are bred …

It is the mind only that makes a king

The kingdom each man bestows upon himself.

Shakespeare never forgot this. The young are sponges, and style is one of the most important building blocks in forming a young person’s taste. However confined his palette, however wearing his repetition of horrors, Seneca has style in spades. Shakespeare’s first youthful tragedy, Titus Andronicus, was pure theatre of cruelty: a young man’s exercise in Seneca as stylish and derivative as a Quentin Tarantino film script.

Genius, of course, is not explicable simply in terms of the accumulation of influences. Roman comedy and tragedy were part of Shakespeare’s diet at school, and with his fabulous memory he

made ample use of them in his professional life. But there was also another dramatic influence from his childhood, which had a more all-embracing effect on his emotional view of his art. The roots of the public theatre in Tudor England lay in a centuries-old vernacular and popular tradition of tremendous dramatic and spiritual power, which was still accessible to Shakespeare in the first fifteen years of his life: the mystery plays.

THE COVENTRY MYSTERIES

Eighteen miles from Stratford – an easy day’s trip on horseback – lay the great medieval wool city of Coventry. From a distance it still bore the marks of its fourteenth-century boomtime: three miles of city walls with twelve gates and thirty-two towers, and the dramatic cluster of church spires and towers – Holy Trinity, St John’s and St Michael’s, whose 300-foot spire soared over the houses, gardens and orchards inside the walls.

In the late 1560s, when William first rode in as a boy, perhaps sitting on the front of his father’s saddle, the place was on its uppers. The third largest city in England, in its heyday it had been home to more than 10,000 people, but after the recession of the 1520s, and the collapse of its old industries, it had seen bitter times. Now local balladeers in the market place sang of ‘dearth and idleness, and little money’. As one Tudor commentator said, ‘This city which was heretofore well inhabited and wealthy … is now for lack of occupiers fallen to great desolation and poverty.’

The Story of India

The Story of India Stolen Children

Stolen Children In Search of the First Civilizations

In Search of the First Civilizations The Murder House

The Murder House A Room Full of Killers

A Room Full of Killers In Search of the Dark Ages

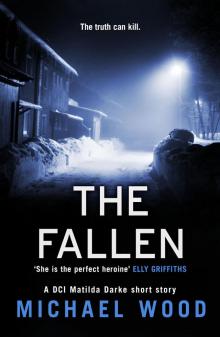

In Search of the Dark Ages The Fallen

The Fallen Time Is Running Out

Time Is Running Out A South Indian Journey

A South Indian Journey In Search of Shakespeare

In Search of Shakespeare The Hangman's Hold

The Hangman's Hold For Reasons Unknown

For Reasons Unknown Outside Looking In

Outside Looking In