- Home

- Michael Wood

A South Indian Journey Page 15

A South Indian Journey Read online

Page 15

Many of the ancient temples in the Cavery valley must have been terrorized at this time, and some of the buried treasure troves uncovered in recent years must represent the desperate efforts of the priests to hide their old bronzes and temple treasures before the onslaught. It is tempting to think that this is the explanation for the great collection of temple bronzes from the eleventh century found in the 1950s buried around Tiruvengadu in the Cavery delta. The eighty bronzes found in a secret room in the 1960s in Chidambaram, which were mainly from the tenth to thirteenth centuries, may also have been concealed at this time. In many cases inscriptions record that a temple had collections of bronzes in the eleventh century which are represented today only by fourteenth-century or later copies. Rajaraja the Great, for instance, had sixty-six bronzes cast for his temple at Tanjore in 1010; of these only two survive today, one a damaged and repaired masterpiece.

As the destruction of the accumulated artistic treasures of a civilization, Kafur’s year-long campaign had few parallels in south Indian history. Are we to see it simply as motivated by greed? Or by religious fanaticism? The work of murderous bigots or of brutal warlords who, as in our own time, from Sudan to Bosnia, have used religion as a means of dispossessing minorities and lining their own coffers? At the time, it must be said, both sides saw the destruction as religiously motivated. The Koran, of course, provides both justification for, and explicit rejection of, such persecution. But for the more orthodox Muslims of the day, holding to the austere monotheism of their sacred book, worship of Hanuman the monkey god or the elephant-headed Ganesh was beyond the pale. However much Hindu philosophers might claim the linga of Siva as an aniconic ‘mark’ of god, in many temples it was all too explicitly phallic. No matter that Muslim and Hindu met in the more elevated doctrines of the Sufis and the bhakti singers; popular Hinduism to many Muslims was irredeemable (as it was to some British imperialists, even in our own century). Stories of the ‘womb chamber’ in Tanjore, where milk libations were poured over a twelve-foot-high polished black stone phallus with head and glans delineated, must have brought shivers of horror among the ulema in the durbar halls of Delhi. No doubt then it was as easy for Kafur to travel with chapter and verse in his baggage as it was for the Conquistadors. The scientist Al Biruni put it succinctly: ‘India is full of riches, entirely delightful, and, as its people are mainly infidels and idolaters, it is right by order of God for us to conquer them.’

In March 1311 Kafur reached the frontier of the Pandyan lands which were then rent by civil war, and marched on Madurai, raiding towns and villages and desecrating temples on his way. Alerted by events on the Cavery river, the priests in Madurai had time to hide their main treasures. The ‘womb chamber’ with the main linga of Siva was filled with earth and bricked up, and a new false linga built outside in the vestibule; scores of bronze processional images were buried; the statue of the goddess was hidden in the vimana, above the shrine; the gold treasures were carried off.

When Kafur reached Madurai on 10 April 1311, like Napoleon at Moscow, he found an empty city, for Sundara Pandya had fled with his family retainers and treasures. The chronicler Amir Khusru says, “They found the city empty, for the king had fled, leaving two or three elephants in the temple of Cokkanatha. The elephants were captured and the temple burned.’ Though the Pandyas were subsequently able to mount a counterattack and forced Kafur to retreat, it had been a disastrous time for the towns of the south, especially for their great and ancient shrines, full of the hoarded-up treasure of centuries. According to a relatively sober source, Kafur retreated with a vast baggage train loaded with loot, including 612 elephants, 20,000 horses and ninety-six measures of gold, the equivalent to 100 million gold coins. ‘At every corner,’ continued Khusru, ‘conquest opened a door to them, and in all that devastated land, wherever treasure remained hidden in the earth it was sifted, searched through and carted away so that nothing remained to the infidels of their gold but an echo, and of their gems, a flaming fire.’

Kafur’s raid was the prelude to an attempt at full-scale conquest and the brief and still obscure period of the Muslim sultanate of Madurai. It is a story which has attracted little attention in modern times; short, brutal and enigmatic, the tale is only now being untangled from the surviving remains of that time. In the following decade the south was subject to more raids; then Muslim governors appear in the Madurai region. In the 1340s these nabobs had proclaimed a sultanate of Madurai, in the story of which the hill of Tirupparakunram played a key part.

When the greatest of all travellers, Ibn Battuta, came here in 1342, he describes the Muslim capital of the south as a large city with well-built streets four miles away from old Madurai by the Vaigai river. His description of the capital matches Tirupparakunram, a Muslim planned town built at the bottom of the great rock. This must be the ‘city of Ma’bar’ recorded by Muslim historians: the capital of the sultanate, during the half century of its life, where eight sultans reigned until the last, Sikander Shah. Indeed, according to local Muslims the tomb on the hill at which they worship is none other than the tomb of this last sultan, killed here in the dramatic battle when the sultanate fell to the forces of the revived Hindu empire of Vijayanagar in 1377

The end of this ill-starred venture, is recorded by the Delhi historians. According to Shams Siraj, the last sultan had gone native, and worse:

He began to perform acts of indecency in public… when he held court in the audience hall he wore women’s ornaments on his wrists and ankles, and his neck and fingers were decked with feminine decorations. His indecent acts with pederasts were performed openly… [and] the people of Ma’bar were utterly and completely weary and out of patience with him and his behaviour. Then the Hindu army from Vijayanagar entered Ma’bar with a large force and magnificent elephants. They captured [Sikander] alive and killed him and took over the city of Ma’bar. They destroyed the whole of Ma’bar, which was a Muslim city, but also the Muslim women were taken by the Hindus. And [their leader] established himself as ruler of Ma’bar.

No doubt we can take the story with a pinch of salt. But Sikander was not the first – nor the last – to go native in the perfumed climate of Madurai. Most celebrated was the Jesuit Roberto de Nobili, who in 1605 donned the saffron and translated Tamil scriptures (the first Westerner to do so), attempting a meeting of Hinduism and the Bible through Christian Neoplatonism and Upanishadic mysticism. For forty years this unlikely figure walked the streets of Madurai with a shaven head and Saivite marks and was a strict vegetarian. He became known as the ‘teacher of reality’, Tattuva Bodhakar (as he still is among the older generation in the city which erected a statue to him not so long ago). It was perhaps the most extraordinary missionary experiment ever undertaken; he only drew the line at offerings to the linga in times of drought. Inevitably in the end the Vatican lost patience with the bold flights of his syncretisms.

There were others. In the early nineteenth century a British collector, Rous Peter, earned the nickname Peter Pandya from the locals for his lavish native lifestyle, his ability to ride elephants and shoot tiger, and his devotion to Minakshi (to whom he gave gifts which are still in the possession of the temple, allegedly for saving his life when a storm wrecked his house). The British were a little more robust about going native, at least in the East India Company days. Peter was remembered as a good chap and elicited admiring comments from the sober author of the local gazetteer a generation later.

It would be pleasing to think Sikander had gone down the same path. But the tradition told today by Muslim pilgrims at Tirupparakunram is somewhat different. To them Sikander was no sybarite or unbeleliever but a pious and saintly king who was martyred together with his faithful vizier and a handful of loyal soldiers surrounded by the Hindu army. His followers’ tombs are pointed out halfway up the hill; his own, on top, is supposed to be on the spot where he fell.

But Tirupparakunram’s pre-eminent shrine is of Murugan; it is one of his six abodes and is mentioned in some of the e

arliest Tamil poetry from the first centuries of our era. This was the goal of our visit: we met up back at the hostel at six and took tea in the lane before making our way to the shrine entrance. The fairy lights on the gopura were still on in the half-light, with the dramatic backdrop of the great rock; at the entrance, the temple servants were washing the steps.

‘This is one of the six abodes of Lord Murugan,’ announced Mr Ramasamy. ‘The legend commemorates the marriage of Murugan to his main wife, Deivani, daughter of Indra. Because of this story, at the auspicious time in early February, thousands of couples come here to solemnize their marriage or to be blessed. Incidentally, as Murugan has a second wife, the wild gypsy huntress Valli, there is also a little shrine dedicated to her on top of the hill, so that she is not left out.’ In the summer, he added, vast crowds attend Lord Murugan’s birthday. ‘Then you will see all sorts of strange happenings: people fire-walking on hot coals, piercing of the body with metal spears and locks through the mouth, people pulling carts hooked to the back.’ He pulled a face. ‘They are all getting a little carried away.’

The main temple is at the bottom, where a town has grown up since the Muslim occupation in the fourteenth century. It is spectacular. Because the sacred core was an eighth-century rock sanctuary a hundred feet above the street, the medieval builders constructed a series of massive terraces to incorporate the ancient features, and you climb through a series of grandiose halls to reach the sanctum.

We entered through a columned hall about forty yards square, supported by a forest of carved pillars. To the left are pilgrims’ stalls, offices and other temple buildings leading to a smaller tank; to the right are further storehouses, including the elephant shed, where the elephant was getting a vigorous scrub from two servants who stood on him, wielding long, hard-bristled floor brushes. The elephant looked up with a beady eye, wriggling with pleasure, as a first rush of early pilgrims came in. While the elephant and I scrutinized each other, Mala hurried over to the office to check with someone from the temple committee that, as a non-Hindu, I would be allowed to go right up to the sanctum. There was no problem: Murugan temples are usually open to all, including untouchables. Most Saivite shrines in the south are also generally welcoming to the respectful visitor, except in big places like Kanchi and Madurai which are on the tourist track. In my experience it is the more orthodox and ‘Sanskritic’ Vaishnavaite temples which invariably refuse entrance to outsiders.

We walked on through the hall. This main mandapa was used as a field hospital by the British when they took the place over in the 1760s, when once more the temple suffered seriously under foreign occupation. It was, said a British observer of the time, ‘the most beautiful rest-house I have ever seen… all hewn of stone with a roof supported upon a number of splendid pillars covered with carved figures… lofty, wide and long’.

At the far end you go under the main gopura and up curving stairs on to the second level and then up two more flights of steps on to the third, where there are a number of shrines. You then climb more stairs on to a fourth level, which leads to the sanctum itself. This is actually built around a series of rock-cut caves dating from the late seventh or the eighth century: at the back of the sanctum are carved panels, black with the constant burning of oil-lamps.

We were among the first people in the central shrine after the temple opened at 6.30. At the sanctum they were getting ready for the first pujas and a very helpful priest explained the rituals: ‘here we only do the libation on the lance of Murugan’ (i.e. the ritual libation); he washed the lance and, after a prayer, placed it on Murugan’s lap. Mr Ramasamy and several of the group including his wife and daughter were with us, and the priest waved us round the rail and into the area of the old sanctum itself, so that we could inspect the carvings close up, including a splendid Siva doing the cosmic dance, watched by Parvati and Nandi. In the main cave facing the entrance were Murugan and Ganesh at the two ends, and the goddess in pride of place in the middle. Below the shrine was a warren of subsidiary caves and long dark passages full of eighth-century carvings which included Murugan on his peacock: all in all one of the most remarkable collections of Pallava sculpture to survive.

He pointed out the line dividing the original rock-cut part from the later additions. For my benefit the priest explained the tale of Murugan’s marriages; everyone chipped in. Mr Ramasamy was a devotee of Murugan; this, after all, was a Murugan pilgrimage including his three major abodes. Mr Ramasamy became animated as he told the story: again the reference to Murugan as the God of the Tamils. Mr Ramasamy speaks of him and the family as if they were rather elevated neighbours, or better still movie stars, the kind of people whose lives and houses are shown off in the Indian equivalent of Hello! magazine, people whose peccadilloes were rather engaging and a constant fund of gossip. Murugan himself was clearly a bit of a lad: ‘This was his first wife, major wife. The second wife Valli was a gypsy; he could go running off to her in the hills.’ He snorted. “This is the prerogative of the god.’ He grinned and rolled his eyes.

‘But why is Murugan a child, Mr Ramasamy?’

‘God can be father or mother. Or a child. When god is a child, the devotee is like a parent and his worship nourishes the child. In return the child gives the devotee joys which a parent has from children.’.

The priest chipped in: ‘This way too the devotee is helped to see himself as a child: to develop childlike skills, playfulness. A child at play is centre of attention, centre of life, worthy of devotion. You see, Tamil people adore children.’

After darshan in the sanctum the priest tidied up. ‘We were occupied by the British. There was a hospital here two hundred years ago. A certain Major Hewitt told his superiors he did not use force against this place, but he did, and a priest committed self-immolation in protest. This was not the action of a British officer and gentleman. Where are you from? London: I have a cousin in Acton.’ Then while Mala and Mrs Vaideyen went for breakfast I headed up the hill path by the temple.

From the top by Sikander Shah’s tomb the plain is spread out before you. It is a lovely spot: some trees in rocky gullies shading a spring, and gnarled and bent umbrella trees bracing themselves against the winds which sweep across the top. On the summit is the tomb chamber and a little mosque with standard fifteenth-century Hindu-type monolithic columns with flowery patterns and brackets. The mosque was added later; it has a domed pavilion on top and a little wooden-roofed colonnade of carved stone columns, again of standard south-Indian type. Probably the tomb was expanded a few decades after Sikander’s death when the Hindu rulers no longer saw Muslims as a threat, and the memory of the terrible attacks of the 1300s had gone. Now a shrine, it is one of the most revered Muslim sites in the region, but you will often see Hindus who have made the climb going in to pay their respects.

The hill of Tirupparakunram is just one of a series of dramatic granite outcrops which fringe the plain of Madurai like enormous boulders left over by some ancient age of fire or ice: Elephant Hill, Snake Hills and so on. In the early morning haze their weird shapes fringe the horizon of the plain like petrified monsters. They are graphically described in one of the first British accounts of the region in 1868. At that time most had never been climbed or visited by outsiders. James Nelson of the Madras Civil Service describes Snake Hills:

They are wild and uncultivated, covered with rocks of all sizes, from stupendous blocks of naked granite down to boulders and stones, and of the roughest and strangest shapes. Only the scantiest vegetation clothes their slopes: thorns and stunted trees alone form their jungles. No wealth of any kind is extracted from their summits and scarcely a pagoda has been built upon them; so that neither the natives who live in their neighbourhood, nor the officers who collect revenues from those natives, are often tempted to climb their gaunt and burnt-up sides.

In the early morning after a little night rain the sky was clear and the air fresh and, apart from a gentle haze over the city, you could see all the way from Tirupparakunram acros

s to the Alagar Hills. The whole of the Vaigai plain stretches out like a natural theatre, widening out into the blue haze in the direction of the sea, fifty miles or so to the east. This was the heartland of Pandya civilization, the southernmost of the three great historical zones of Tamil Nadu, the sacred landscape which animates the temple myths of the Pandyan land. Looking from the top of Tirupparakunram, modern suburbs stretch out across the plain on both sides of the Vaigai river, and in the centre, visible despite the early morning haze, are the four main gopuras of the Great Temple of Minakshi, which lies at the heart of one of the oldest and most famous cities in the whole of south Asia: Madurai.

THE GREAT GODDESS OF MADURAI

We headed in along the long straight road from Tirupparakunram and soon hit the teeming streets of Madurai. Home to a million people, the second city of Tamil Nadu after Madras, it is a thriving commercial city, famous for its textile mills and transport workshops, and has a very busy shopping centre. The streets were blocked with lorries, cycle rickshaws and bullock carts. Auto-rickshaws buzzed like angry hornets. Marco Polo spent two months here in 1273, not long before the Muslim sack, and called it ‘the most noble and splendid province in the world’. Polo got hot under the. collar about the scantily clad women, for it was the custom for women to go bare-breasted, as it was even recently on the nearby Malabar coast. Today the city is as famous as in the Venetian’s day for its commerce and in particular for its quick-witted street sellers and rickshaw-men, who are proverbially out to con the unsuspecting strangers and country folk, who pour in in their thousands every day to do pilgrimage to the goddess of the ‘fish eyes’.

The Story of India

The Story of India Stolen Children

Stolen Children In Search of the First Civilizations

In Search of the First Civilizations The Murder House

The Murder House A Room Full of Killers

A Room Full of Killers In Search of the Dark Ages

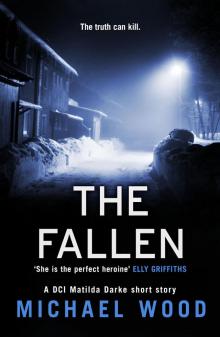

In Search of the Dark Ages The Fallen

The Fallen Time Is Running Out

Time Is Running Out A South Indian Journey

A South Indian Journey In Search of Shakespeare

In Search of Shakespeare The Hangman's Hold

The Hangman's Hold For Reasons Unknown

For Reasons Unknown Outside Looking In

Outside Looking In