- Home

- Michael Wood

A South Indian Journey Page 16

A South Indian Journey Read online

Page 16

The bus slowed down to walking pace behind a ruck of bullock carts. ‘Mr Michael, be very careful with your money here,’ said Mr Ramasamy with a concerned look. ‘People here are out to bamboozle you. Not as bad as Delhi, but this is the reputation of Madurai; watch your purse. Don’t be persuaded to buy things; they will have the very shirt off your back.’

Madurai is booming these days. New buildings are going up everywhere. The entire place is being rebuilt in concrete, with a profusion of new hotels near the station, but the modern city is shaped by the ancient. The streets form a series of concentric circles around the temple, a layout which has always determined the city’s topography and which probably goes back at least to the first centuries AD. The inner streets are named after the Tamil months and were part of the ritual layout of the city from its earliest days; this is planning as laid down in die religious texts for the sacred city, the cosmic city. It is an ancient idea you can see in ruins at Teotihuacan in Mexico or as a museum in the Forbidden City, but here it is still living.

Madurai in fact is one of India’s oldest cities, mentioned in Indian and Greek texts from the fourth century BC onwards. From the first century BC, when Greek navigators discovered the secrets of the monsoon, their merchants could sail regular return journeys every year to trade in spices; soon they started to settle in Madurai. In Tamil sources the Greeks here are described as mercenaries living in some sort of colony. Epic poems refer to the Yavanas – the Greeks – walking the streets gawping like tourists. There are even tantalizing references to Greek sculptors working here. Hoards of Roman coins have been picked up in the city and across Tamil Nadu, proof of commercial links with the Roman empire, and these are detailed in one of the most fascinating documents to survive from the ancient world, the Alexandrian merchants’ manual known as the ‘Periplus of the Erythraean Sea’.

Following leads from the ‘Periplus’, Mortimer Wheeler excavated in a creek near Pondicherry on the eve of the Second World War, and uncovered the Roman warehouses of Arikamedu crammed with Aretine wine for the Tamil middle classes (a first-century consumer boom?). In Augustus’ day a Pandyan embassy went from Madurai to Rome, and soon enough a temple to the emperor was erected on the Kerala coast at Cranganore. (Victoria was not the first Western ruler to have her statue set up in an Indian garden.) The biggest demand on the part of Western consumers was for spices. If we are to believe the geographer Strabo, in his day the Roman balance of payments ran deeply into the red to fill the pepper barns by the Tiber’. And even today some of our words for spices – pepper and ginger, for example – are loan words from Tamil which came into Western speech via Greek.

The cultural pre-eminence of Madurai dates from this period. Tradition holds that the city was the centre of the Sangam, or academy, of Tamil poets. In Tamil literature there are, in fact, legends of still earlier, antediluvian sangams, but the one in the Roman period is real enough. A famous Sangam poem, ‘The Garland of Madurai’, paints a brilliant image of the city in the days of the second-century Pandya king Nedunjeliyan when, it was said, the perfume of flowers, ghee and incense from the city could be smelt from miles away: ‘a city gay with flags, waving over homes and shops selling food and drink; the streets are broad rivers of people, folk of every race, buying and selling in the bazaars, or singing to the music of wandering bands and musicians’. The poem describes the stalls round the temple, ‘selling sweet cakes, garlands of flowers, scented powder and betel pan’, and the craftsmen working in their shops, ‘men making bangles of conch shell, goldsmiths, cloth dealers, tailors making up clothes, coppersmiths, flower-sellers, vendors of sandalwood, painters and weavers’. All this could be today’s city, and indeed Madurai has known an amazing continuity from that day to this; the Pandyan dynasty had its ups and downs, but a distant scion of the dynasty ruling in Strabo’s day was still ruling when the British Raj took over in 1805.

We parked by the north gate and walked round to the east entrance usually used by pilgrims. Here custom dictates you enter not under the gopura but through the goddess’s mandapa, the hall where the eight attributes of the goddess are represented. Where Chidambaram is the god’s house, this emphatically is the domain of the goddess. The road outside is crammed with shops and stalls hung with decorative canopies. Here at festival time the streets are closed to traffic and you cannot move for stalls selling clothes, shoes, tools, utensils, tiffin boxes, toys, cakes, scaly-skinned jak fruit. Right by the entrance are tea shops with old brass samovars where they boil up the first brew at four, just as the temple is opening. Behind the shops is one of four big covered stalls where the thousands of visitors leave their shoes before entering the shrine.

Before you go in, just opposite the entrance, there is a grand mandapa built as a choultry for pilgrims between 1626 and 1633 by Tirumala Nayak, the great builder of early modern Madurai; beyond the temple are the remains of his Nayak palace, constructed in a showy Saracen Gothic. He also built the huge festival tank outside the old city walls. But the mandapa is perhaps his most magnificent, and certainly his most tasteful piece of work: 333 feet long and over 100 feet wide, it has four rows of elaborately sculpted monolithic pillars supporting a flat roof of huge granite slabs; in the central aisle are portraits of the dynasty. A haunting series of glass-plate photographs – now in the India Office library in London – taken in the 1850s by Captain Edward Lyons, shows this wonderful building at the time of the Indian Mutiny, unencumbered, its floor an undulating expanse of polished flagstones. But for a century now the building has been leased to tailors and the place is packed with stalls, shops, workshops and booths heaped with bales of cloth, curtained with figured drapes. Walk through here any time of day and you will be besieged by importunate seamsters offering to run up a suit for you by the end of the day – or sooner. It can be a struggle to stay clothed.

‘Hello, sir. Kindly tell me what is your native place? You are from which country? England? Very nice. I have many English friends. Do you know Hull? I am a tailor, sir.’ (Hands card.) ‘Seven generations of my family are tailors here by the East Gate. Come into my shop. Sit; sit and have some tea. No obligation to buy. Just look.’

He stared at my shirt.

‘This is a very old shirt.’

‘Actually it’s a very new shirt. I got it as a Diwali present. But it has only taken the dhobi in Chidambaram one wash to beat the life out of it and break all the buttons. I think the dhobis and the tailors must be in cahoots.’

He laughed. ‘Dhobis are tailors’ best friend, sir. But you are most definitely needing a new shirt. If you will take off your shirt here and now, I will measure and copy it by five clock. Exact. I will make two: one white, one blue. Best Kanchi silk. No? You don’t want shirt? Look, your trousers have ripped. These I can remake.’ (Takes tape measure from round neck and threatens inside leg measurement.) ‘What time does your tour bus leave? I will bring them to your hotel. Take them off straight away! Take them off please!’

‘I’m sorry. I’m going to the temple now to do puja. I can hardly visit the goddess with no trousers.’

‘All right then, what about a sari for your wife?’

‘This is not my wife.’

‘No problem, sir. Still you can take a present for your wife too. Maybe you want to change dollars? Very good rate. Better than Indian State Bank. Pounds? Deutschmarks?’

As he ran after me his voice dropped to a hissed whisper: ‘You want some nice Kerala grass?’

Above you smile voluptuous, life-sized, stone goddesses adorned in real saris, rouged in vermilion, cooled in sandal. Below, the aisles chatter and rattle all day and half the night with the sound of treadle sewing-machines.

Leaving the mandapa and coming back to the east entrance, the one traditionally used by pilgrims, we plunged down the steps into the goddess’s entrance hall. It has an arched roof supported at the sides by double rows of columns on stone platforms above the pavement. The front rows have carvings of the eight attributes of the goddess; these a

re life-sized granite caryatids with powerful shoulders, muscular breasts, elaborate suspenders and freshly vermilioned foreheads. Above is a clerestory of painted stucco figures; the ceiling is gaily painted with flower designs enclosing five yantras, ornamental mandalas peculiar to the goddess. At the inner end are stone statues of Ganesh and Murugan, the children of the goddess whose house we are about to enter. Tied up framing the entrance were fat stems of banana plants, sagging under tumescent bunches of green fruit: everywhere images of fecundity.

The entrance literally seethed with life. Set back behind the columns were brightly lit stalls selling all the usual offerings for puja. Through it you come into what is almost a town within a town, for the outer halls of the temple are given over entirely to commerce. Even if you have seen it all before on the Tamil pilgrim trail, as I had, still the pilgrim stalls of Madurai come as a staggering spectacle: you pass through caverns of bangles in coloured glass, plastic and cheap gilt and walk down arcades of gaudy religious pictures, showing gods and goddesses of every faith, and some unheard of. Airbrushed eyes follow you round under cascades of travel bags, peacock feathers, clockwork birds and fluffy toys. There are trays of conch shells, emeralds, beads, sandal bars. There are heaps of the most dazzlingly intense scarlet, saffron and purple powders (on one table alone I counted a dozen dizzying shades of crimson). In the central colonnades are twenty or thirty flower stalls piled with beds of cut flowers, and hung with garlands as tall as a man, kaleidoscopes of cut blooms individually strung and bound to make adornments fit for the necks of politicians or gods. Around them the floor was littered with leaves, discarded blooms, broken coconuts; the air was drenched with the perfume of jasmine and incense. Finally, at the central crossing, you stop under four vast bracketed piers, and stand rubbing your eyes trying to take it all in, while the crowd jostles past you into the interior. Then you feel a soft moist breath tousling your hair and look up to see two temple elephants standing benignly over you, bright yellow yantras of wet sandal on their foreheads. Shifting gently from foot to foot they receive the pilgrims and their proffered rupees amid a cacophony of noise, chatter, laughter and music, while sudden flurries of drumming and squeals of trumpets echo in the depths of the interior. And we had yet to set foot inside.

Mala came over to pull me away from the pictures and brusquely handed back to the stallholder the one I was about to buy, a silver-framed trio of lissom young goddesses sitting lotus fashion in red saris in a crimson-draped boudoir. (By now I confess, I was becoming irresistibly hooked on the most tawdry superficialities of Hinduism.)

‘It’s really nice, don’t you think?’ I said hopefully. It cut no ice with Mala. ‘He is charging too much. Twenty-five rupees is too costly. Now we are going in. Put it down and come.’

I protested feebly and then did as I was told. A few days on the road and we were beginning to behave like a married couple.

In Madurai, contrary to the usual custom, the goddess is always worshipped before the god. As far as the pilgrims are concerned, this is her temple, not his. And so, offering baskets in hand, Mala and Mrs Vaideyen led the way past the Ganesh shrine which stands in a lovely little garden opposite the elephant house. The paving-stones were damp after their early morning wash; a kolam on the floor, fresh marigolds on a cluster of lingas and snake stones under the vanni tree. In the garden a group of pilgrims were reading religious texts aloud with their guru. In the early morning light under a clear blue sky the temple looked simply lovely.

From everywhere you can see the gopuras. These form the distinctive skyline of the city. Madurai city laws forbid building higher, as also does old Tamil popular belief. ‘Building higher than the temple gopura is a proverbial description of hubris. That day the west and south towers were covered with scaffolding, wooden poles and wicker cladding – undergoing a major renovation, the first in thirty years, to restore and repaint the sculptures on the towers. There are no fewer than 1500 sculptures on the south tower, and the west and east towers have over a thousand each. Now faded to a pleasant pastel shade, they are to be restored to a garish Hindu Disneyland, as we could glimpse from the glaring tangerines, greens and kingfisher blues under the rattan screens.

Here the Tamil gopura reaches its apotheosis, sweeping up in elegant parabolic curves covered with sculpture from top to bottom. There is none of the restraint of Chidambaram, with its sedate measured rows of dignified deities; here they are swarming with demons, gods, goddesses, monsters, animal-headed creatures, figures of myth, fantasies, dreams, nightmares, wriggling, prancing, dancing – giving the impression of a myriad life forms. Energy itself shooting up into the sky. Here you think that if Zen is about the distilled essence of life, Hinduism is about its amazing and infinite variety. Or, as Edward Lear put it when he came here in 1874, ‘its myriadism of impossible picturesqueness’.

It is not everyone’s cup of tea, it must be said. Though an artist like Lear could describe the Dravidian temples as ‘stupendous and beyond belief, this architecture was disparaged by the architectural historian Ferguson, who raged at its barbarity, finding it all a prodigious wasted effort, and to make matters worse, ‘all for a debased fetishism’. He thought nothing here aspired to ‘the lofty aims of the best works of the Western world’, and reserved his most scathing comments for the design of the gopuras: ‘As an artistic design nothing could be worse,’ he thundered. ‘The bathos of the gopuras decreasing in size and elaboration as they approach the sanctuary is a mistake which nothing can redeem; it is altogether detestable.’ As for the idea that ‘the altar or statue of the god should be placed in a dark cubical cell wholly without ornament’ – well, that left him finally speechless. ‘If only the principle could be reversed,’ he burbled, ‘such buildings would be among the finest in India.’ Which only goes to show how even the best scholars can utterly fail to escape the preconceptions of their own time and culture, and, what is worse, fail completely to divine the purpose of the architects who made these great buildings.

The temple forms a rectangle about 850 × 750 feet on its longest sides, so it is by no means the largest of southern shrines, but inside this is the final baroque flowering of the Dravidian style we saw in an earlier phase at Chidambaram, and whose origins lie in the seventh-century shore temple at Mahabalipuram and the early shrines at Kanchi. Inside you enter a labyrinth of corridors around the shrines, monolithic sculpted granite columns thirty feet high, with huge stepped overhanging brackets to carry the roof, many of the columns highly sculpted into the form of monsters and capped with the snapping heads of mythical beasts. Leading off the corridors are many sub-shrines, including the thousand-pillared hall built in 1572, which is no longer used for worship now. About 250 feet square, it has 985 granite pillars brilliantly carved with mythological figures. A wide central nave leads to a shrine of the dancing Siva, with vistas down the full length of the hall. At the far end a large bronze Nataraja is now inappropriately backlit with Hammer House of Horror red gels.

In front of the main shrines the corridors open out into pillared vestibules in the ‘baroque’ style of the Nayaks. Most impressive is the Kambattadi mandapa, a vast shadowy arcade in front of the entrance to the Siva shrine. Lit by dazzling shafts of light from the roof, this space has the baroque magnificence of the contemporary Bernini. But where the Italian master constructs floods of light with gold, paint and sunbursts of gilded wood, here the astounding elaboration of the carving (and in such a hard stone) is coupled with a sensual energy which positively bursts out over the iron rails. Such was the last flowering of the Pandyan tradition. Though in fact only erected in the early seventeenth century, it actually looks as one might imagine the House of Atreus had it never fallen; smelling of hoary antiquity and glistening with vermilion and the oil of sacrifice.

Originally, the mandapa was lit only by artificial light – the light wells, like the neon strips, are modern – and you passed this lamp-lit zone before plunging down the axis to the silvery chamber of Siva, whose starry lamps fli

cker deep in the interior. In few architectures has the world of the spirits been made so concrete. In front of you, rearing up behind iron rails, are the twenty-four forms of Siva carved in the round on the sides of eight huge pillars around a tall gilded flagstaff which rises through the roof. Among these is the marriage of Siva and Minakshi–Parvati, which is still celebrated every year. Between them, facing Siva’s sanctum, is his faithful bull Nandi, a stone monolith which is usually covered in heaps of darba grass and a snowfall of salt offerings.

This colossal arrangement is faced by another group of four monolithic granite statues each over ten feet high, and each a masterpiece of the stonecarver’s art. There is Siva in his fiery ‘terrifying’ and ‘non-terrifying’ forms, the urdhva tandava (the impassioned dance), and also Bhadrakali, the ever-present black incarnation of the goddess. These statues are the object of much veneration for today’s pilgrims, and in front of them there is always an attendant seated at a little table with a large tin bowl containing lumps of ghee floating in water (to stop it melting in the heat). These the. pilgrims buy for a few paise and throw at the statues for good luck; it is an ancient custom but no one could enlighten me about its origins. By mid-morning the figures are spattered head to foot with yellow ghee, which is scraped off every hour or two by temple servants on ladders.

The mandapa creates a tremendous brooding impression: the dim light, the giant statues, the lamps and puja fires, the glint of brass and silver, the shafts of sunlight coming down from the light wells, not to mention the noise and the smell – an impression quite overwhelming to earlier generations of visitors, who rather like Forster’s Miss Quested entering the Marabar Caves, found it all ‘frightening’ and ‘incomprehensible to the Western mind’. Hinduism here was ‘a religion without possibility of salvation’. Francis Yeats Brown, a well-known thirties Indophile, could not bring himself to enter (‘I was afraid’). ‘Here one may see the very essence of Dravidian idolatry,’ wrote one old British hand in the twenties, admitting nevertheless that ‘the whole effect upon the mind of this majestic hall is powerful and strange in the extreme’.

The Story of India

The Story of India Stolen Children

Stolen Children In Search of the First Civilizations

In Search of the First Civilizations The Murder House

The Murder House A Room Full of Killers

A Room Full of Killers In Search of the Dark Ages

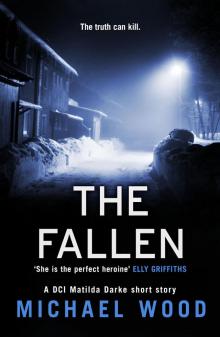

In Search of the Dark Ages The Fallen

The Fallen Time Is Running Out

Time Is Running Out A South Indian Journey

A South Indian Journey In Search of Shakespeare

In Search of Shakespeare The Hangman's Hold

The Hangman's Hold For Reasons Unknown

For Reasons Unknown Outside Looking In

Outside Looking In